In March of 2020, which now seems like a lifetime ago, I gave a talk at QCon London called “Remote Working Approaches that Worked (And Some that Didn’t)”. By then I’d be working 100% remotely for ten years, first as a CTO for a start-up which was subsequently acquired, and then as editor-in-chief for C4Media’s InfoQ. My feeling was that remote working could be generally positive for both employee and employer, and I wanted to see more of it.

I got my wish.

But whilst the world has undeniably shifted to remote working, it was done in a rush and without much planning. Initially, this worked out fairly well, driven by a willingness to try to make the best of a bad situation. However, we have over a century of experience working in offices to draw on, whereas remote working only started in the 1980s, and we’re still figuring out how to do it effectively. Moreover, like all aspects of organisational culture, remote culture requires thought, and I worry that as the willingness to make the best of it fades, companies that have switched permanently to being remote may come unstuck.

That would be a huge shame. Remote working is better for diversity, (including neurodiversity), and opens up a range of opportunities for organisations that simply aren’t available any other way. It allows you to hire teams with specific specialisations based on geography, makes it easier to scale hiring processes, and opens up options for people who might be able to work eight hours a day but maybe can’t do so in one continuous chunk.

It isn’t without its challenges though.

Previously on WTF, we have tackled some key questions through pieces including “A Psychologist’s Guide to Reconstructing Work for a Virtual Future World”, “How to Make Hybrid Meetings Not Suck” and “Hybrid Remote Work - Think Bridges, Not Destination”. In this piece I want to explore a different problem: working remotely introduces an additional layer of complexity around keeping a company focused.

Setting priorities

If you’ve ever worked at a small but growing start-up you’ve likely come across an inflection point when you can no longer interact with everyone and employees don’t know who everyone is. Exactly where that point is naturally varies from company to company, but in my experience, it is typically at around 100 people. As an executive or senior leader, this can also create feelings of uncertainty about your own role. Container Solutions is at this inflection point and is feeling some pain and working through it. Jamie Dobson, co-founder and CEO at Container Solutions says

“It’s difficult for me to be in all places at once. I used to be able to do that better. So it feels like something’s changing.I am momentarily unsure of my role. I, like the organisation, am going through a transition myself. It's a step into the unknown. Scary and exciting."

When this happens you start needing to add more processes and policies, which can itself be fraught. But you also have a second problem which is “How do you keep everyone aligned and working towards the same company goals?” And the answer, which sounds impossibly glib, is you need to be very clear about what the goals are.

When I worked at C4Media we tackled this by adapting the approach from Verne Harnish’s book “Mastering the Rockefeller Habits”. You can find a good, quick summary of the book here.

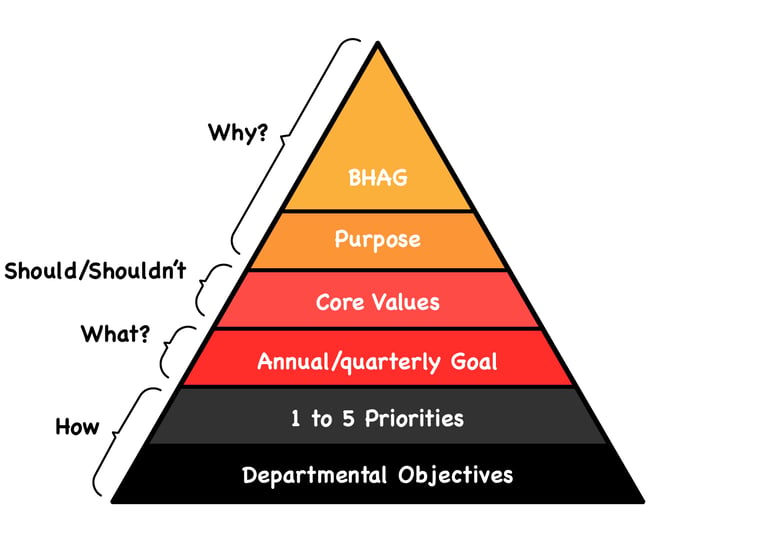

Alongside the ten habits, Harnish suggests a basic structure, which I thought of as being a hierarchy.

At the top is the company’s long-term goal—something that is expected to take decades, is clear and compelling, and needs little explanation. Harnish calls this the BHAG (pronounced ‘Bee Hag’”, short for ‘Big Hairy Audacious Goal’) taken from Jim Collins et al’s book “Built to Last”. Collins uses the original NASA mission “to put a man on the moon and bring him back safely,” as an example. It’s compelling, but I’d also point to the one Bill Gates gave Microsoft in 1980: ”A computer on every desk and in every home”. As Gates later noted, “It was a bold idea and a lot of people thought we were out of our minds to imagine it was possible. It is amazing to think about how far computing has come since then, and we can all be proud of the role Microsoft played in that revolution.”

Your BHAG doesn’t need to reach quite these levels of audacity, but it should give you something definite to aim for. Ideally, it would be something you could measure. One of the important things a BHAG does is act as a filter, reminding you not to get distracted by tempting ideas that don’t align with what the company is trying to achieve.

Once you have a BHAG it does need to be clearly and repeatedly communicated—particularly as you scale up and new people join the company.

Below the BHAG you have your purpose, also known as the “why” for your company. The combination of the BHAG and the company purpose should also act to provide employees with their sense of purpose, which Dan Pink’s work (often remembered by the short-hand “autonomy, mastery, purpose”) suggests is one of the key things that motivate people.

Next are the core values for the organisation. Core values are particularly valuable in smaller companies, but they do require you to enforce them properly. Regrettably, this does sometimes require firing employees who don’t match those core values; failing to take action on this tends to have an outsized effect when there are relatively few people.

I’m aware that some of this sounds awful—the sort of thing that you can produce from an auto-strategy generator—and I’ll admit that I initially rebelled against them. With experience though, I’ve found that when done well the combination of BHAG, why, and core values provide sound guiding principles for the organisation and end up being surprisingly effective.

With those set, Harnish suggests that the executive team “set priorities—no more than five—and then identify the one goal that supersedes the others. This is known as the top 5, or 1-5 priority list.”

These will change based on your planning rhythm but will typically be annual goals. The very action of whittling down the list of priorities will itself help you find some focus, and the ensuing debate can help bring clarity.

These priorities then need to be recorded somewhere that everyone in the company has access to. This brings us to a key point about being remote—a successful remote culture requires a strong written culture. At C4Media, we did this through a one-page plan (another Harnish idea) that in our case lived as a Google doc. As well as BHAG, purpose and core values, a one-page plan should include 3-5 year targets, 1-year priorities, and quarterly objectives. It should also include top-line financial information such as revenue, profit, gross margin and so on. I’d personally also recommend including an indication of cash-in-bank here, and revenue per employee or EBITDA as this is a useful number to keep an eye on as you start to scale.

With the organisational priorities set, departments and individual employees can then set their priorities and see how they match the organisational goals, which gives you a key alignment tool.

Giving everyone access to the one-page plan brings us to our second key idea, which is that remote cultures have to be high trust cultures. You have to be able to fundamentally trust the people that work for you remotely because you can’t see what they’re doing, which means they have to feel safe to tell you. That trust starts at the organisational level—not the individual employee level—and is something you have to exhibit rather than communicate. At C4Media, one of the core values, transparency, was explicitly chosen to re-enforce it.

Another way of thinking about trust is that you need psychological safety for a remote culture to work—something we actively promote at Container Solutions. Google’s Project Aristotle, which has done much to popularise the concept in business, defines it thus:

"In a team with high psychological safety, teammates feel safe to take risks around their team members. They feel confident that no one on the team will embarrass or punish anyone else for admitting a mistake, asking a question, or offering a new idea."

Google famously found that psychological safety is the number one factor in high performing teams at the firm, and whilst you absolutely can have high performing teams without it, I would argue that psychological safety is essential in remote cultures.

With that all in place, you need to continually reinforce it … with meetings.

Meeting rhythms

Something that commonly happens in all-remote companies is that the number of meetings seems to grow exponentially. If you are working across timezones those meetings tend to bunch around fairly narrow windows. For example, if you are based in London and working with someone in San Francisco, your meetings will tend to be mostly in the evening, and theirs in the morning. In addition, your days may end later and later, and theirs start earlier and earlier to fit them all in. As a side note, this is worth thinking about when deciding where you can hire people—I’d recommend a maximum of around five hours across a team.

Having a fixed structure for meetings ultimately reduces the amount of time you spend in meetings. As a basic guiding principle, I’ve found the following rhythms effective.

In-person meetings

Every remote company I’ve worked at, and everyone I’ve talked to in the course of exploring this topic, has found that they need some in-person meetings. There are two which I would recommend if at all possible.

Annual all company

C4Media would get the entire company together once a year for 3 days of in-person meetings. These were the highlight of the working year for many of us, and typically produced a tremendous amount of energy and enthusiasm around what the company was trying to achieve. An example format might be:

1 day of formal presentations—update from the founder and an opportunity to reinforce values and purpose, plus updates from each of the major divisions.

1 day of open-space meetings.

1 day of sightseeing or similar.

Quarterly or bi-annual departmental planning meetings

Ideally, these should be in-person as well and 2-3 days in length. For tech teams, the focus will often be on a key product decision that ideally maps back to one of the top five priorities.

One company I talked to had a less formal approach, where they would hold in-person meetings as they were needed. Typically this would also be around 2-3 times a year but not on a fixed timetable. Regardless of the exact process, these meetings are necessary and the company will need to budget for them.

Virtual

Monthly all-hands or town hall

The town hall meeting provides an opportunity for you to talk about progress against the company goals, and for employees to ask questions. In large group settings employees can be reluctant to speak up, so at Container Solutions, we use Slido to allow anonymous questions. Anonymity can bring with it the worst kinds of unsafe behaviour, so

expected standards of conduct do need to be reinforced.

Weekly team meetings (virtual)

These will usually be around 30 minutes to 1 hour long.

For the weekly WTF is Cloud Native meeting, we use the following format:

1. Check-in—5 mins

2. Numbers and pipelines (next 2 months)—15 mins

3. Customer & employee feedback—5 mins

5. AOB—5 mins

There are a couple of important things to note from this format. The first is the check-in. Each individual’s check-in can be either work-related or personal, but the goal is that everyone gives a quick update on how they are doing. From a manager’s perspective, this gives you an opportunity to model vulnerability. We’ve noted already that transparency isn’t communicated, rather it is imitated. So, as a manager, you have to be transparent to cultivate a transparent company. You might say, for example, “I have some unidentified health problems at the moment. I’ve got to go to the hospital next week. I’m a little bit frightened about it.” By doing so, you’re making it clear to the people that work for you that it is alright to be a bit vulnerable, to be a bit exposed, and then they will be more willing to do that for you.

I’ve used two different formats of check-in: the formal format from The Core Protocols version of “I am sad/mad/glad/afraid because this happened” can work well in some teams, but I favour a more informal version, which is just, “This is what’s going on in my life” or “This is what’s going on at work”.

The second thing to note is the emphasis on feedback. Spending 5-10 minutes reviewing specific feedback from both customers and employees, anonymised where appropriate, will tell you what issues keep cropping up, and what people are hearing.

Stand-ups (virtual)

For the Container Solutions marketing team the stand-up is used primarily for dealing with blockers rather than as a status update. We find we don’t need it every day—twice a week is sufficient.

One-on-ones (virtual)

We’ve talked about one-on-ones on WTF before, but I want to re-emphasise them because they are one of the most important meetings you can have as a manager.

A one-on-one meeting is not a status meeting. Rather it is your opportunity to find out what’s really going on for your employees, where they want to go, and things like career development. As a manager, you have people’s careers in your hands. There’s a handy managers’ maxim that people join companies, but they leave managers, and they’ll leave you if they don’t think their career is going to progress. One-on-ones are also the best place to collect individual employee feedback to pass back to the wider team, anonymised where appropriate.

I recommend having a repository of shared notes, and Google Docs is good for this.

Camille Fournier’s book, “The Manager’s Path” has good advice for one-on-ones, including lots of information about different styles of one-on-ones and how to mix them up a bit. If you find that one-on-one meetings are all getting a bit samey, it’s a really good book to refer to for advice.

Communication

I’ve never worked in an organisation larger than 30 people that didn’t have communication challenges. The problem is exacerbated by working remotely because casual, “coffee machine/water cooler” conversation doesn’t happen.

What I’ve seen happen in remote organisations around this point is:

a. A chaotic plethora of different communication channels erupts.

b. Meetings, particularly status meetings, multiply to take over much of the day.

How many different communication channels do you currently use for work? 15Five, Email, Zoom, Slack, JIRA, Confluence, Twitter, WhatsApp? Each tool you add introduces additional cognitive stress. If you find yourself thinking “I know Jane sent me something on this but where the hell was it?” several times a day, you’ve got too many tools. Unless guided otherwise, people in remote teams will just often use whatever tools they like the best. But, as Lissette Sutherland notes in “Work Together Anywhere” “communication works best when a team agrees on a tool—and the etiquette around that tool—and then sticks to that agreement.”

At Container Solutions, a combination of 15Five, Slack, Jira, Confluence, Google Apps and Google Meet does the trick:

- 15Five works best as a status reporting tool and allows you to remove status reporting from other meetings such as stand-ups, which can instead be used to focus on unblocking.

- Slack is used for general coordination and is generally preferred over email for internal communication.

- Jira is used for planned work, as well as things like purchase orders and so on.

- Google Docs is used for more major project tasks. For example, I coordinate all the work for WTF using a Google spreadsheet.

- Google Meet is used for meetings.

Some Common Anti-patterns

A final thing I wanted to cover in this piece is some of the anti-patterns I’ve seen at different remote organisations.

Centralised Command and Control

There is a risk when applying the Rockefeller Habits, that you end up having the executive team over-dictate—in essence, work is determined in a centralised headquarters and is then doled out to individual employees. Of course, this isn’t exclusively a problem of this methodology: it’s a common issue with any founder or exec team who doesn’t want to let go—Randy Shoup observed the same issue at eBay for example. However, it is something to watch out for and to guard against. As an executive or an engineering manager, your goal should be to give your employees direction and then let them find their path. The more autonomy you can give, as Dan Pink notes, the happier they will be.

Overly-long meetings

Some things are really a struggle to do remotely. Asking people to spend more than about an hour on video is asking a lot. Expecting that to happen late into the evening, and/or trying to do strategy meetings this way is, in my experience, just a waste of everyone’s time. For longer meetings, and in particular, for anything that requires a strategy discussion, batch them up and do them in-person over a couple of days.

Some things are really a struggle to do remotely. Asking people to spend more than about an hour on video is asking a lot. Expecting that to happen late into the evening, and/or trying to do strategy meetings this way is, in my experience, just a waste of everyone’s time. For longer meetings, and in particular, for anything that requires a strategy discussion, batch them up and do them in-person over a couple of days.

Out-of-date documentation

We’ve noted that a remote culture requires a strong written culture, but that introduces the problem of ensuring documentation is kept up-to-date.

The best advice I can offer on this is to make sure you have enough documentation but not too much, and that you review it regularly—2-3 times a year for any living document works quite well. Again, if you have a high-trust organisation, allow anyone to edit any document—that way, if someone spots something inaccurate, they can fix it.

Bringing it all together

Stepping up a level, the common thread that ties all of this together is the importance of trust. A remote culture will only work well if people can speak up, amend things, and correct problems as they go.

As managers and executives you need to provide direction—what is it that we want to achieve—but then you absolutely must step back and allow the people you’ve hired to do the work and to actually solve problems.

A well-designed structure—including a BHAG, company purpose and core values—supports greater individual and team autonomy, thereby increasing motivation and leading to higher performance across the organisation.

At Container Solutions, we’re making several changes that are specifically designed to help us as we scale up. From a process perspective, we’ve recently brought in peer reviews, structured pay rises, and career ladders.

From a management perspective, we’ve made changes to the structure of the Executive Team, based on the idea of functional accountability. “Our original executive team was just not representative of the whole company and several departments were not represented,” Dobson explained.

"So we created an executive team from a broader cross-section of the company, (marketing, salespeople, finance). What we’re trying to do there is put everybody at the table, to further democratise decision making and further represent the company.

But it’s not just the personnel changes we’ve done there. That team meets every Monday—you could call it a huddle or a weekly planning session. They meet again on Wednesday for 20 minutes. And then monthly reports to me with an updated dashboard, ‘This is what we’re doing. These are some of the challenges we’ve seen.’ We always believed in those Rockefeller habits, working in sprints, looking back every few months to figure out what was going on. But this is the first time we’ve managed to get a cross-functional and diverse executive team pulsating in that cadence."

In terms of the hierarchy, Container Solutions started with a strong purpose but has done a poor job of communicating it. Dobson recalls that

"There’s a nexus of so called “soft” stuff: ambitious goal or wider purpose, five-year objectives, values, vision, and mission. We got busy defining and regularly communicating the values as a group last year. We have to get busy quickly specing out what our purpose is and talking about it constantly in exactly the same way we’ve been speaking about values. So, if there’s a checklist of things to do, we need to get to that next step and start ticking those boxes.”

If you want to join us on our journey we are hiring!

Previous article

Previous article