In its Aristotle project, Google tried to define the success of effective teams. The researchers’ main finding was that what really mattered was less about who is on the team, and more about how the team worked together. Most important in teamwork was the presence of psychological safety.

‘There’s no team without trust’, says Paul Santagata, Google’s Head of Industry.

In my previous blog post, we explored what it means to be a learning organisation, and how important such a culture is to Cloud Native companies. Learning organisations need to foster psychological safety, or the shared belief that a team is safe for interpersonal risk taking. This means that the members of the group believe no one will be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, concerns, or mistakes.

In an environment where psychological safety is the rule, team members worry less about the potential negative consequences of expressing a new or different idea than they would otherwise. As a result, they speak up more when they feel psychologically safe and are motivated to improve their team or company. Psychological safety differs from trust due to the focus: trust is about the individual, whereas psychological safety is about the group belief and is only experienced in a group.

Your Brain, at Work

Ancient evolutionary adaptations explain why psychological safety is both fragile and vital to success in uncertain, interdependent environments.

When you’re provoked by a bullying boss, competitive coworker, or dismissive subordinate, your brain processes it as a life-or-death threat. The amygdala, the brain’s ‘alarm bell’, ignites a fight-or-flight response, hijacking higher brain centers. This ‘act first, think later’ brain structure (also called the limbic system) shuts down perspective and analytical reasoning. Quite literally, just when we need them most, we lose our minds.

While that fight-or-flight reaction may save us in life-or-death situations, it handicaps the strategic thinking needed in today’s workplace.

Research has found that positive emotions like trust, curiosity, confidence, and inspiration broaden the mind and help us build psychological, social, and physical resources. We become more open-minded, resilient, motivated, and persistent when we feel safe. Humor increases, as does solution-finding, experimentation, and divergent thinking—the cognitive process underlying creativity.

When the workplace feels challenging but not threatening, teams can sustain creativity and innovation. Oxytocin levels in our brains rise, eliciting trust and trust-making behavior. This is a huge factor in team success, as Santagata, the Google executive, attests: ‘In Google’s fast-paced, highly demanding environment, our success hinges on the ability to take risks and be vulnerable in front of peers’.

Balancing Safety and Accountability

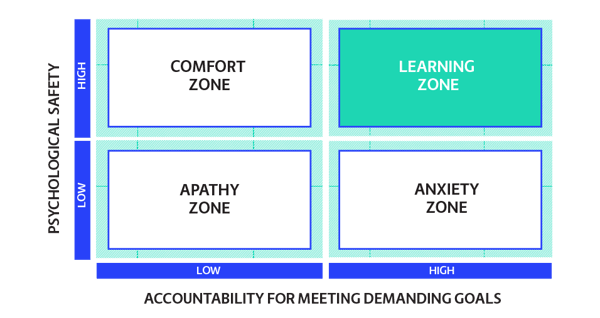

Most managers think that with psychological safety you lose the ability to hold people accountable. This is a basic misunderstanding. Psychological safety is not about lowering your standards of performance but it is all about enabling candour and openness in order to set ambitious goals. It enables a more honest, challenging, and collaborative work environment where innovation can thrive.

In the figure shown, we see the two equally important dimensions: psychological safety and performance standards (accountability) and how they can interact together, creating different ‘zones’.

Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson’s work explains what each of the four zones could mean in a workplace.

Learning Zone

When people experience high psychological safety, and standards are also high, we see a learning zone. The learning zone produces a high-performing team, especially when the outcome’s uncertain and team members rely heavily on each other to get their work done. It gives team members room for asking questions and invites discussion.

Anxiety Zone

Leaders who only hold their employees accountable, having high standards but lacking the psychological safety, fall into the ‘anxiety zone’. This is a ‘danger zone‘ because potential errors and mistakes are not reported, mostly due to fear of humiliation and criticism. When errors or failures are not flagged because people are too scared to speak up, they can have devastating and sometimes deadly effects, like the 2003 explosion of the Columbia Space shuttle.

Comfort Zone

The comfort zone is characterised by high safety: This means people feel free to express their concerns and have open discussions. But because of the lack of accountability, these teams will typically not be high performing.

Apathy Zone

When people have low standards for performance and teams don't experience much psychological safety, the workplace can become ‘apathetic’. Employees will come to work, but won’t have their hearts in it. They will use every means available to gain or achieve something for themselves: they stop sharing and working together.

Thinking: Fast and Slow

It would be great if we could use our rational brain to determine the level of risk when faced with a new situation or a crisis, right?

But there’s the problem: We don’t. Instead, we more commonly use our instincts and emotions —remember that ‘alarm bell’ in our brains, that ‘fight-or-flight’ reaction? And when we think or recognise a certain situation that has happened before—and went wrong— we are more likely to overestimate the likelihood that that same situation will happen again.

We shut down. We can’t solve problems creatively or be innovative. Fight or flight.

This difference between our instinct brain and our rational brain is what Daniel Kahneman, a psychologist and an economist and author of ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’, describes as System 1 (emotional, instinctive) and System 2 (logical, creative) thinking.

We have the two systems in order to use our brains as efficiently as possible: our System 1 is efficient and takes little effort; we only activate System 2 when required.

So when it comes to risk assessment, we need to push ourselves to not react quickly and unconsciously, but to force ourselves to think more analytically. We need System 2 thinking, and the innovation it produces, to reduce risk.

Innovation, Risk, and Uncertainty

How are risk and innovation related? For starters: risk pushes innovation. For example, the risk of contracting diseases, like polio, or the measles, prompted the innovation of vaccines.

For a company, the risk of losing customers to a disruptive competitor also pushes innovation. But it’s not always clear as to what and how to innovate: Our future is hard to predict. What direction will the next innovations take? Who will benefit? What will be the impact?

A mere 15 years ago, who could have predicted the rise of Uber, or AirBnB? Certainly not the taxi or hotel industries.

With so many uncertainties and risks in their future, how can an organisation, especially a Cloud Native company, prepare to seize opportunities and adapt to changing conditions? You need a team that can continuously learn from its mistakes, and continuously improve: a learning organisation, built on psychological safety.

5 Steps to Create a Climate of Safety

So, how can companies start creating psychological safety? Here are five ways to start fostering this group belief in your organisation:

1. Frame the Work Accurately

People need a shared understanding of the kinds of failures that can be expected to occur in a given work context (routine production, complex operations, or innovation) and why openness and collaboration are important for surfacing and learning from them. Accurate framing detoxifies failure. This is even more so important in Cloud Native transformations, where most work from the outset is iterative and complex.

2. Embrace Messengers

Those who come forward with bad news, questions, concerns, or mistakes should be rewarded rather than shot. Celebrate the value of the news first and then figure out how to fix the failure and learn from it.

By using the system of ‘blameless reporting’—an approach that encourages employees to reveal errors and near misses anonymously— we can collect more data on failures that pushes us to learn.

3. Acknowledge Limits

Being open about what you don’t know, mistakes you’ve made, and what you can’t get done alone will encourage others to do the same. Make simple statements that encourage peers and reports to speak up, such as, ‘I may miss something—I need to hear from you’.

Also, asking for feedback on how you delivered your message opens the conversation and because you show vulnerability you are able to become more aware of your own blind spots, in for example your communication skills. Modelling this fallibility increases trust in leaders.

4. Invite Participation

Ask for observations and ideas and create opportunities for people to detect and analyze failures and promote intelligent experiments. Inviting participation helps defuse resistance and defensiveness.

We have learned that failure and fault are inseparable, admitting you have failed means taking the blame. This is why it is so hard to shift to a psychological safe environment where learning from failures can be fully utilised.

5. Set Boundaries and Hold People Accountable

Paradoxically, people feel psychologically safer when leaders are clear about what acts are blameworthy. And there must be consequences. But if someone is punished or fired, tell those directly and indirectly affected what happened and why it warranted blame.

Hope you found this useful. To delve deeper into the concept of a learning organisation, go back and read my previous blog post on that topic.

Previous article

Previous article