In medieval times, there was a mythical land of Cockaigne in popular culture that served as a fantasy for the hungry masses. In this land, physical comforts were always available, and the harshness of life was banished. Plentiful food and drink was a pleasant thing for a starving peasant to contemplate as she stared at her thin broth in a cold hut in darkest winter.

We no longer collectively dream of Cockaigne. (Most of us in the developed world find it all too easy to get fat.) But most enterprises in the 21st century might well fantasize about not having to worry about where revenue and profit are coming from.

A Mountain of Cash

Some enterprises are indeed in this position, and can make money without much effort. Perhaps the most well-known money-making machine of this type is Google. The company's advertising revenue from search products means that it could simply do nothing and continue to make significant profits for a long time.

Why is this a curse? Because nothing lasts forever, and while Google may be king of search now, there’s nothing to stop it from being banished in the coming years to the recycle bin of history along with AltaVista and Yahoo.

A manager we spoke to about his experiences as a middle manager at Google said: 'It’s hard to argue for change in a company with 100 billion dollars in the bank'.

If a business is a proven success, then getting it to change in any respect is going to be extremely difficult. The evidence of success is sitting in the bank, and this does not promote the reflection required to motivate real change.

The sheer march of time is itself a threat to your business, and demands change and adaptation to meet it.

‘Curse of Plenty’ Anti-Patterns

So what to do about this? On the one hand, you are aware of a threat requiring change, and on the other, you don’t want to hurt your cash cow. In other words, you lack a real existential threat that motivates real change.

At Container Solutions, we see this pattern frequently: A senior executive team demands technological change in the face of some distant but very real threat. The threat might be disruptive challengers in your industry that pose a small but growing threat to your business, or that your traditional customers are dying off and not being replaced by a younger generation.

Unfortunately, what to do about this threat is not clear. Anti-patterns we see include:

Lack of resilience

Regardless of why a Cloud Native transformation—or any transformation— is initiated, when the going gets tough it can be tough to keep going. At that point, if you suffer from the Curse of Plenty, then it can be easy just to give up and abandon all attempts to change. However, if the world is still moving on, then your reasons for initiating change in the first place have not gone away, and you are further away from dealing with the threat.

Case Study 1: Abandoned Cloud Platform

A large bank’s board decided that it needed to exit its data centres, so embarked on an ambitious strategy to do so, ostensibly to save money. After three years, a completely original universal platform was built that satisfied the regulators. However, to get there many compromises were made, and the board decided that it was too difficult and expensive to achieve the original goal, and effectively disbanded the team.

When an ambitious goal is set, it is easy to give up on the whole effort when it turns out to be more difficult than originally anticipated. In this case, a team with unique and deep experience in solving a problem that will become common in banking and finance in the coming years was expensively built and then discarded, effectively wasting any value generated from the investment.

The ‘cargo cult’ transformation

Organisations can often feel that they must initiate a Cloud Native transformation because they believe others in the same space are doing so also, or already have. This is a kind of FOMO (fear of missing out) that can result in half-hearted attempts at transformation that wither in the face of the inevitable challenges that arise (see ‘Lack of resilience’).

In such cases, an organisation might simply copy what others have done, without figuring out what works and what doesn’t in their context. The hard work of making change work within a specific context results in a collective learned experience that cannot be replicated by just copying the perceived behaviours that result.

This kind of behaviour is often called ‘cargo cult transformation’, after the description of ‘cargo cult science’ popularized by the physicist Richard Feynman. The original ‘cargo cults’ were behaviours designed to reproduce desirable outcomes from past events. For example, Melanesian islanders built fake airstrips in an attempt to get the Japanese and American airplanes that had previously dropped off valuable supplies in World War II to come back. By building the fake airstrips, they thought they would get the same outcome as before.

In recent years, many IT transformations have achieved a similar effect by copying the Spotify model, with its Guilds, Tribes, and Squad structure. While the Spotify model can work for many organisations, it is unlikely that simply naming a group of employees a ‘Tribe’ is going to fundamentally change anything about the way those people work.

Lack of existential ‘event’

If you haven’t experienced an existential threat, then it can be hard to summon the energy to make the changes you need, especially if the business is currently a financial success.

Case Study 2: Blockbuster Video

In 2000, the then-dominant 15-year-old video chain Blockbuster was offered Netflix in a $50m sale. The CEO of Blockbuster tried not to laugh at the unreasonably high price, and the negotiation ended there. At the time, Blockbuster had about 7,000 stores worldwide and was still growing. Ten years later, Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy, and the last store closed in 2014, while Netflix has a market capitalisation value of $160 billion.

This is an example of a successful and growing business failing to take seriously enough a need to change. In 2000, Blockbuster was blind to the reality that they were ten years from bankruptcy, and even had another six years of growth before the game was up just four years after that.

Lack of management cohesion

Without a clear business need to change, retaining the level of unity among senior management required to sustain the focus required to support the rest of the business can prove difficult. The transformation agents end up spending so much time playing politics that they get burnt out, frustrated, and give up, or get disillusioned and leave.

Outsourcing responsibility

One tempting approach is to hand over responsibility for making the change to a third party, who you can then blame if things go wrong. The old saying ‘You never get fired for hiring IBM’ could equally be applied to the big names traditionally involved in change management.

Engaging a third party can work if senior leadership retain ownership of the result, and collaborate with the service providers to work through the challenges that transformation brings. But if your company’s executives don’t take ownership of the project, then the entire effort can be wasted.

Innovator’s Dilemma

Readers of Innovator’s Dilemma may recognise these concerns. In that classic business text, Clayton Christensen describes the challenges facing enterprises that dominate an existing market from present and future threats through technology. He looks closely at two apparently very different industries (disk drives and mechanical diggers), and draws common lessons for other technology firms.

Interestingly, the prescription of the book is not simply to transform quickly, or always invest in whatever is new or innovative. If done too early, or in the wrong manner, misdirected investment can result in even more wasted opportunity. Examples of these abound, from Polaroid pioneering the digital camera in 1975 to Xerox Parc’s innovation spree earlier that decade. Both organisations failed to see the path to profitability of their own innovations, causing that innovation effort to effectively be for nought.

Conclusion

When you suffer from the ‘Curse of Plenty’, you can fall victim to your own success. A mountain of cash, market dominance, or a golden money-making product at the centre of your business can all encourage you to ignore longer-term threats that may require transformative effort to address. This can take several forms, including:

- A ‘cargo-cult’ transformation by numbers

- Outsourcing the responsibility for the change

- Giving up on change when the going gets tough

- Half-hearted attempts at innovation that are not supported and pursued

Next: In Part 2, we look at patterns you can use to facilitate change while suffering from the Curse of Plenty.

Illustration by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, from "The Land of Cockaigne." Photo by Dwight Burdette. Both licensed by Wikimedia Commons.

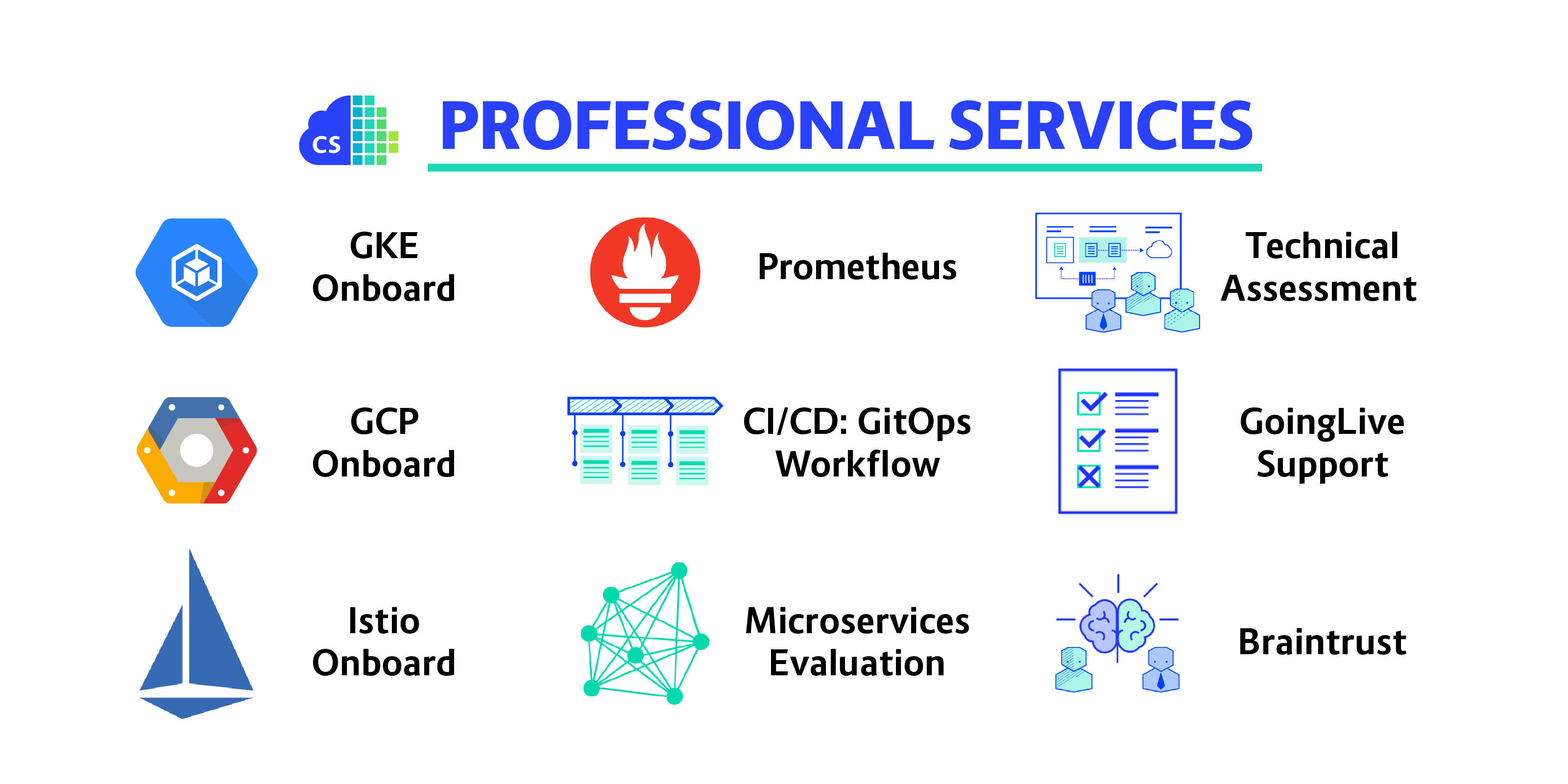

We love leading our clients through a Cloud Native transformation from start to finish, but we also now offer six service packages, each of which can be completed in anywhere from two to six weeks. Click below to check them out.

Previous article

Previous article