Container Solutions started 2020 with plans to double our revenue, continue our expansion in the United States, and launch our latest service to help our customers migrate to green data centres. Things were going very well.

One week in March brought all our plans to a stop.

On Thursday in that fateful week, I found my agenda and to-do list empty. Alone in my kitchen, sitting on one of the children’s chairs, I started to cry. There are 100 people who work at Container Solutions, many with mortgages, many with children, and all of whom put their heart and soul into their work. The job of leading them through the COVID-19 crisis would fall to me.

It was a job for which I feared I was not ready. At home, I have four children, including twin babies who, at the time, were 10 months old. I had no idea what we were going to do should Container Solutions fail.

As I sat there, I felt my world collapsing around me. I felt an overwhelming sense of shame. Every ancient inadequacy and insecurity washed over me. That intolerable, enduring thought, the burden of my whole life, and the source of all my restlessness, would not leave me. My choices would evaporate and with them my freedom. Poverty beckoned.

So I cried.

10 minutes later, a wiser internal monologue took over. Will we just curl up and die? Is all hope extinguished? Did I really think this is a tough challenge?

This last one was a particularly good question. Even though the COVID-19 crisis would unfold to be the biggest crisis we’d ever faced, we had spent the past year building our skills and capabilities. So we faced COVID with much more confidence than we’d faced, for example, a pretty awful cash flow crisis in January 2017 and the loss of a key client in 2019.

I realise, now that I have had the chance to look back, that on that day my ‘process’ had begun in earnest. Shock and shame came first before giving way to questions and remonstrations. I can’t repeat what I said to myself, but suffice it to say, these remonstrations brought me back, mentally, to where I needed to be.

From there, the open-ended, hopeful questions started to emerge. What, if anything, can we make of this situation? What new skills will we get a chance to practise? A thought appeared: forget the revenue, forget the growth, in fact forget all financial metrics because 1. They are as good as gone, and 2. The balance sheet can always be rebuilt, and instead focus on the group. What will we learn? How will we grow? What garbage can we jettison?

Accepting Reality

A couple of hours later, my wife, Andrea, came home and asked me how I was. I said I was fine. I picked up four cans of Stella from the cornershop and slept well that night. I slept well because I had made peace with the demise of Container Solutions. I knew that none of us would be able to think or operate at speed unless we accepted the seriousness of the situation and the potential of death. There was no time to bargain, no time to prevaricate, no time for self-pity.

In this regard, we were lucky; we had quickly grasped the scale of the challenge and we would go on to use this to our advantage. We’d given ourselves a few days to absorb the shock and one day to grieve. By then, at the end of Friday, 13 March, we knew what we had to do. It would be another 20 weeks before I’d cry again.

Framing the Problem

With the exception of the little hiccups in 2017 and 2019, none of us at CS really have much experience of crisis management. What we do have are three key processes that allow us to revise our plans in real time, and those proved to be invaluable. Unfortunately, we didn’t have manuals, guidelines, how-tos, frameworks, templates, or anything that would allow us to get started quickly.

So, as the COVID crisis began, I did what anyone would have done; I Googled ‘crisis management’ and then went onto Amazon and ordered a set of books.

We took three immediate and useful heuristics from them, each of which would help us frame how we managed the unfolding crisis:

Crises come in four stages.

The first stage is the preparation phase, where the seeds of the crisis are sown. The second is the crisis itself, whose end we can’t know in advance. The third is the resolution, which comes when we can say with some confidence, ‘the crisis is over’. Finally there is the learning stage, where the crisis and our response to it are unpacked and lessons are learnt.

Time and information are scarce.

To make decisions, you need information and the time to analyse it. In a crisis, you have neither.

It’s basically project management.

It turns out crisis management is basically project management but with less information and more empathy. There are tasks that need doing and following up on, communications that have to be timely and sensible, etc. However, it all must be done with extra empathy and compassion. Why? Because people are rattled. So whilst it’s true, your balance sheet might be getting battered, it also true that human beings are as well.

All of this gave us confidence. Firstly, the seeds of how we’d survive the crisis had been sown earlier, with our execution framework and cash management. We didn’t know it in advance, but we found out we’d prepared well.

Secondly, we know very well how to operate with limited information because that’s exactly what a start-up does and we’d only just left the start-up phase. All we needed to know was our runway (the amount of cash we had left) and work backwards from that. There’s not a single person at CS who does not understand this.

Thirdly, since the last stage of a crisis is learning, we had something to look forward to, some sort of prized wisdom that would lay at the back end of this shower of shit.

Finally, in regards to empathy and compassion, these are as close to second nature to us as YAML files are to a Cloud Native engineer. We founded this business to be different to what we’d experienced in our careers previous to Container Solutions: to have empathy, compassion, and growth built-in, and not some sort of weird bolt-on.

Moving Fast, Flying Blind

One way to make quick decisions is to have a value system. When you operate from your values, you don’t need as much information; in lieu of information, you simply fall back to what you care about.

Container Solutions is a values-driven company. This meant, for example, in our first COVID-related meeting as a management team, we discussed redundancies—but not for long. We value sharing, and togetherness, and fairness. Therefore, to make people redundant would have gone against everything we cared about.

By living our values, we were able to quickly shut down one set of scenarios (thus saving time and energy) and focus instead on much more constructive scenarios, such as raising capital, progressive salary cuts, costs cutting, and calling in favours.

That being said, no matter how useful values are for decision making, they are not enough. Therefore, from our values, we quickly threw together a few rules for the crisis. These rules would evolve and grow as the crisis unfolded:

No bystanding.

We will not point out the failures of those who are making decisions in real time with limited information.

We rise and fall together.

The idea that our fates are bound is a strong one at Container Solutions. That would not change during the crisis. We even spoke about the ancient idea of ‘nemo resideo’—leave nobody behind. (Throughout the crisis, we would repeatedly turn to philosophy and science fiction as we dug deep into our reserves to find meaning in what we were all going through.)

Use empathetic responding.

We value ‘other-focus’ at Container Solution. However, our colleague, Helen Bartimote, our lead psychologist, would teach us about ‘empathetic responding’, which would let us evolve our understanding. (More on that a bit later on.)

Designing Action

As a further aid to decision making, we plotted actions that would preserve our culture against actions that would preserve our financial health. The idea here was not to trade financial health for cultural health but to seek actions that would help with both.

Again, guided by our values, we agreed that if we were given a choice between cultural health and financial health, we would always prioritise our culture.

This allowed us to do certain things. For example, by deferring our tax payments, we could put off using the furlough scheme in the United Kingdom until the last possible moment (even though we’d one day have to pay the tax bill). By renegotiating our agreements with our supply chain, we could preserve our cash and our relationships. By speaking to our board and issuing new shares, we could avoid a later cash-flow crisis. In other words, we designed our actions based on these rules in this specific order:

- Take actions that preserve the culture and preserve the balance sheet.

- Take actions that preserve the culture.

- Only if there are no choices, take actions that preserve the balance sheet.

Drawing from our values, in the first few days, and on the fly, we’d framed the challenge, come up with guidelines for the group, and a prioritised list for how we’d design action. This was far from complete but it was better than nothing.

Empathetic Responding

We knew instantly that COVID-19 would create a mental-health crisis. Therefore, during the initial burst of planning and reframing, and as the finance team busied themselves desperately to defer tax payments, our psychologists sprang into action.

The result of this work, led by Helen, would be our COVID-19 mental-health guidelines. Soon after, we would share them publicly. It was through this work that we evolved our idea of other-focus, adopting what Helen called ‘empathetic responding’. Here is what our guidelines say about this:

In times of crisis and threat, research shows that people will tend to respond in one of three ways, with some being more helpful than others:

- ‘I wish this would all just stop’ … ‘this will blow over soon’ = Wishful thinking, and means you will be less likely to engage in health-related behaviours.

- ‘I need help from you as I cannot cope with this myself’ = Support seeking, or excessively relying on others for emotional support. It is important to reach out to others in times of crisis, while at the same time being mindful of the impact this may have on the people around us.

- ‘I would like to help you’, ‘what can i do to support you?’, ‘I wonder what I can do to help my community with this?’, ‘I wonder how this situation is making X feel?’ 'How could I help?’ = Empathetic Responding, which is generally considered to be the most effective for communities and also for an individual’s own psychological well being.

We had never considered that helping others would benefit our own psychological well-being. Helen provided us with this powerful insight. This nudged us into doubling down on trying to help other people. Internally, we all asked, ‘How can I help?’ and ‘What can I do?’ The idea being that if we all help other people and other people help us, we’d bolster our psychological well-being whilst moving tasks forward. A win-win.

At the same time, we asked our customers, What do you need? Some needed to pause their work with us. Others, for example in retail, needed to speed up.

What did our community need? Good content. Friendly faces. Hope but not false hope. A way to use this enforced downtime wisely. With that in mind, we started offering training for free, webinars for free, sharing daft videos (like my Duke of Wellington one from Greenwich park) and throwing together a Software Circus conference, themed around Alice in Wonderland.

Software Circus itself was amazing. Earlier in the day, I had opened the conference with Mark Coleman, Software Circus’ co-creator. Later, we had music, comedy and fancy dress. I actually had other things to do but I could hear Andrea downstairs listening and laughing so then I jumped back in. Later on, I tried to work again but somebody would send a message on Slack, ‘so and so is talking on track two’, and so we’d all jump in again.

At one point, I gave up on trying to work and just sat back and enjoyed the moment. At about 3 o’clock, I had a pint of Stella. Then another. I WhatsApped Mark. I said, ‘Mate, I think I am pissed here, I’ve had two pints’. To which he replied, ‘Mate, I started drinking at lunchtime!’ And then, like a total pro, Mark continued hosting the conference until 10 O’clock that evening, when it eventually closed!

We had, for just a day, brought the community back together and in doing so brought ourselves some much needed respite.

Salary Sacrifice and Capital Raise

On 20 March, eight days after I cried in the kitchen, we had the first all-hands meeting of the crisis. Moving forward, we would meet weekly and I would give updates on Slack daily.

In that first meeting, we focused on the initial steps we had taken, a 12-week timeline, a reminder of what is expected in terms of bravery (we expect tons of it), and bystanding (we expect none of it).

We also announced a temporary new structure. Ian Crosby, our managing director in Canada, would take over engineering as our interim CTO. Everyone else on the executive team would focus on sales and customer support, with the exception of our CFO, Kristian Ladefoged, who would focus on stretching our cash reserves. The idea was that, once we rebuilt the sales pipeline, no salary-cutting measures would be needed or taken. The summary slide laid out what had to happen:

We had a plan. It lasted three days. Shortly after that all-hands, in the second week of the crisis, we lost more contracts. The original €4.2 million loss became €6.5 million. At the same time, all our sales conversations stopped. The world had frozen.

Since all costs were cut and all government schemes applied for, we had only one major cost left: our salaries. We needed to cut our wage bill by about 25% in order to build a bridge over the summer into September. This was a sickening moment. But the decision itself wasn’t hard. In fact, it wasn’t a decision at all. We could lay off about 25% of the workforce or we could share the burden, as we’d already said we were going to do.

That week, in the all-hands, we announced that everyone would take a salary cut and that the amount would be progressive. The high earners would sacrifice 30%, average earners about 25%, and interns and any exceptions (such as those with challenging personal financial circumstances) would not sacrifice anything.

With the exception of two people, everybody bought into this plan. Nobody complained. I had hoped for a positive response but would never have dreamt of such an overwhelming one. The culture we built had just been tested. We passed. (Later in the summer, many people would tell me that this was the proudest moment of their careers. We also spoke about this at my birthday drinks in August and people started crying again.) This was our first jaw-dropping moment.

It was at this point in events that things got… interesting. About four days later, we held an emergency board meeting. It was clear we had to stretch our cash as far as possible. Therefore, in that meeting the shareholders agreed to issue more shares, which we’d sell only to either our staff or friends of the company, such as our advisors.

When we spoke to our bank and explained our plans, the bankers were impressed. Firstly, by our decision making and our plan and secondly, by the board’s decision to issue shares. They saw us as a team that made decisions quickly. Because of this, our bank extended our credit facilities, thus stretching our cash further. The extra credit facilities made those thinking of investing, such as our advisors, more confident that we were on the right track. We’d created positive momentum.

Internally at CS, we started to host small roundtables. The roundtables were both a crash course in finance for our fellow CSers and an explanation of what we’d do next. If people wanted to invest, they could fill in a form to show their interest level. They could buy stock in cash or salary sacrifice stretched over the coming year.

Then something started to happen: before the second roundtable started, we had received a set of forms from the first roundtable. By the time the last roundtable happened, we had more than €1 million committed to the round. Within days, we had exceeded our goal of €1.2 million. A few weeks later, when the funding round was closed, we had in our bank €1.4 million, all of it made up of small investments from our people. Overnight, and thanks to the crisis, we began to realise a long-running dream to make Container Solutions employee owned. This was our second jaw-dropping moment.

We started to think our crisis strategy might just work.

End of Round 1

Within 12 weeks, we had restored the salaries. In that time, we had been laser focused on stretching the cash, raising capital and maintaining psychological well being. Once all of that was in flight, we then turned to finalising a new option scheme. Everybody in the company received 500 options, which are instantly convertible to stock should CS be acquired. We of course accept that you can't go on holiday with options. However, we saw the issuing of the options as step 1 in making the salary sacrifice right. It is of course another step towards employee ownership.

The first part of the crisis was about to end. By a miraculous combination of goodwill, talent, advice, good fortune and, frankly speaking, creative desperation, we had fixed a number of problems. The bleeding had stopped, the bridge to September was built and salaries had been restored. We had enough capital to survive even our worst case scenarios. At this point, Kristian and I had not had a day off. We had worked for 84 days in a row.

Too Soon to Declare Victory?

That Friday, I may have been happier and may have had more than four cans of Stella, but we were miles off resolving the crisis because the cash reserves would evaporate in no time if we did not rebuild our sales pipeline. That job would fall to a new, larger leadership team that was born out of this crisis. This team had been appointed a few weeks earlier.

As the crisis unfolded, it uncovered hidden leadership within Container Solutions. Specifically, Jade Amic, Carla Gaggini, Russ Trow, Cameron Wood, Svitlana Chunyayeva, Andrea Dobson, and Andrea Beltran all reacted well. They remained calm under pressure, acted quickly, took vague objectives and made them concrete. They became rocks for their teams, some of whom experienced sickness, some of whom in the U.K. were furloughed. They did this whilst they had to look after kids in lockdown (four in the case of Andrea Dobson), cancel new house purchases because with their reduced salaries disqualified their mortgage applications, nurse (and reassure) pregnant wives and mourn the passing of relatives.

Throughout the crisis, I had been reading about competent and incompetent leadership. I started with On the Psychology of Military Incompetence, continued with a biography of the first Duke of Wellington, and wrapped up with Why Do So Many Incompetent Men Become Leaders?.

One reason incompetent men get promoted is because they invest more than others in image management— that’s a nice way of saying, they bullshit their way into positions. Through lobbying and charisma, they win everybody over. However, when these incompetent men actually have to lead, the delight of their peers slowly turns to disappointment and even horror as it dawns on them what a catastrophic error in judgement they have made.

This was the opposite of what happened at Container Solutions. Our emerging leaders didn’t get their jobs by managing their images. When the crisis hit, they didn’t vanish. They stepped up.

At this exact moment, I was reading The Ikea Effect by Anders Dahlvig. I took two things away. Firstly, in his position as CEO, he’d circumvented normal procedures to install two female executives on his team. He had worked with them, vouched for them, and wanted to take immediate actions to address the gender balance of his team.

Secondly, he ran a monthly meeting where he, his executives, and the layer of managers below would meet. This way, they didn’t waste time passing messages. If they met more often, he said, then the meeting would naturally be about operational stuff, which is not what he wanted to talk about with his top team. Executives who needed more steering, he said— for example, in a weekly meeting—were not fit to be executives and should be removed.

On Friday, I spoke to Pini over drinks - something we only do when there's something serious to discuss. The following morning, I got my book out and sketched out the new structure, preempted any questions I might get, and made a plan. The next week, after speaking to each person, I announced that, for the duration of the crisis (and if it works, indefinitely), Jade, Carla, Russ, Cameron, Svitlana, Andrea Dobson and Andrea Beltran would join my team. Like Dahlvig, we had circumvented normal procedures. This was one example of a key leadership quality: when the circumstance calls for it, you have to be willing to act autocratically.

This is not the same as being an authoritarian, someone who loves and therefore seeks power. It’s about, when you have to, making a decision and owning the consequences. You usually become an executive because you have good judgement and moral courage. Every now and then you have to use this power, making sure you don't ever abuse it.

When there’s no time, you have to back yourself to make decisions. If you have a track record of prioritising the needs of the group and apologising when you’re wrong, they will in turn back you.

New Ideas: Engineering and Marketing

At the top of the crisis, our Canadian managing director had stepped into the then empty role of CTO, taking the position in the interim. Ian’s job was to try and organise engineering as best he could, support the team there, and make sure they got what they needed.

Like the marketing team, those in engineering were working tremendously hard. Those with customers billed as much as possible, since we needed the revenue and our customers needed their projects moving along. This was especially true for our retail customers who were dealing with massive increases in load. Those engineers not with customers teamed up with the marketing team, delivering webinars, blogs and, in the case of Ian Miell, a whole new book on GitOps. It was an epic response.

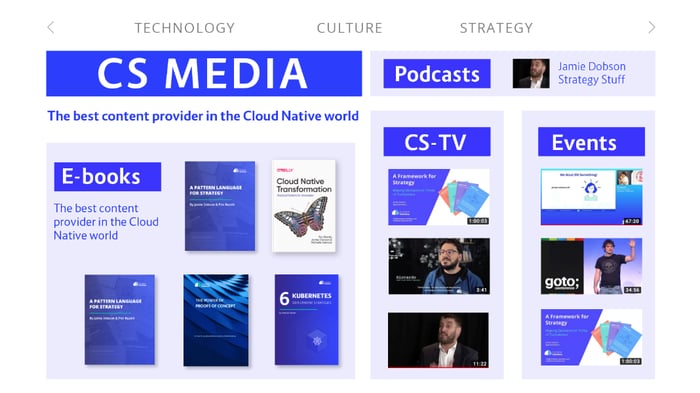

Earlier in the year, across the organisation, but mainly where engineering and marketing intersect, we had started to gestate a new idea: CS-Media. The idea behind CS-Media was to take all the work we do, and especially all the client work we do, and communicate that to a global audience. Here is an early concept:

They say that war is history’s fast-forward button. Well, it turned out that the COVID pandemic was our fast-forward button. CS-Media, being too dry for a bunch of very tired people who had given up on filtering themselves, was renamed to What the Fuck Is Cloud Native?

WTF Is Cloud Native would become our new, never-ending quest. It would take the shape of a media company that had the singular focus to ask and re-answer the question, WTF Is Cloud Native? This is our magic trick in action, once again. Serving the content needs of others bolsters our own well-being. It is, however, very clearly a way to enhance our brand and generate leads, which we have to do if we’re to rebuild the sales pipeline.

We can already see that September will be our single best month for visitors to our site. The extra activity is combined with two new hires, Felix, to manage our partners, and Adrian, to work alongside Greg in sales, where their job is to help our followers on their Cloud Native journeys.

Will this work? Time will tell. The best we can do is stack the odds in our favour, which we felt we have done. We hope by mid-October to see our pipeline looking like it did back in March.

The Aftermath

Once we had gotten through the worst of the crisis, we tried to start to wind down. Our psychologists and managers had done an excellent job of support to those who needed it. But we were tired and desperately needed a break.

On the 9th and 10th of July, we took a company-wide mental health break. At the same time, we introduced no-meeting Wednesday. Everybody loves this, including me. (This is now a rule at CS and we don’t intend to change it back.) Finally, the whole company took every Friday in August off. Those who could, took a vacation. The end of the beginning was in sight.

We said in the all hands, back in March, that it’d be a 12-week job to get on top of the COVID pandemic. In the end, it took 20 weeks. What had we achieved?

We maintained our mental health.

We had, just, managed to keep sane. There were tears. There were disappointments. There was fear. There was grief. But we shared as much as we could and stuck to empathetic responding. Through the diligent work of our managers and psychologists, where possible, we reframed the trauma of the crisis as a crucible in which we could grow.

We restructured the company.

In the past, we had sometimes promoted the wrong people. Learning from these lessons, we ran an internal selection process to appoint a new CTO. Ian Crosby, who had been appointed interim CTO at the start of the crisis, got the job permanently. Michael Müller would move from his role of managing director of our Germany office and take the new role of Chief Customer Officer, making sure that we helped our existing customers.

In engineering, Ian introduced engineering managers, two new roles, and worked with Adrian Mouat to organise our open-source initiatives. I still have the same number of reports, but now work every month with a wider group that includes Jade, Carla, Russ, Cameron, Svitlana, Andrea Dobson and Andrea Beltran. We are proud of our work here; this is another example of just how willing we are to experiment with hierarchy-busting techniques.

We are employee owned.

Seventy-six percent of Container Solutions is now owned by those who work in it or on it. As part of that restructuring, we raised €1.4 million in capital. As a group, we now share the downside risks and the upside rewards. This is a dream come true for us.

We launched WTF.

COVID gifted us two things; a tiny amount of a time and a mountain of pressure. This gave us creative desperation. That desperation pressed the fast-forward button, allowing us to accelerate WTF. Through WTF, now being prepped for a proper rollout in a few weeks, we will engage the community. It has also helped us rebuild our lead generation system from scratch.

Playing the Hand We Were Dealt

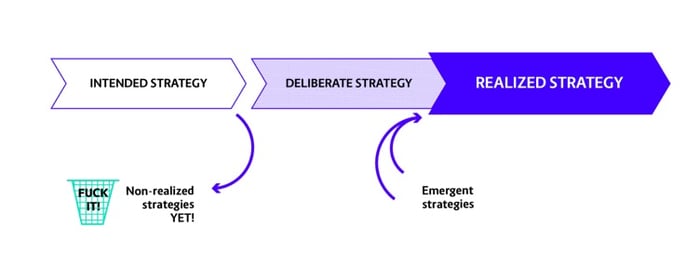

At the start of the crisis, we asked the most important crisis-question a company can ever ask. If we project 12 weeks into the future, what gifts do we hope this crisis can give us? Working back from there, what do we have to do to achieve it? We knew what we wanted from this crisis. This was our intended strategy.

However, we had no idea we’d restructure the leadership team and no idea we’d raise a round of funding. These strategies arose over the first eight weeks. Eventually, they joined with our original strategy to give us what we have now, our realised strategy. That’s why our strategy only looks coherent in retrospect.

This ability, to integrate new ideas into our plans, is probably the thing that Container Solutions does best. It’s not just that we are curious, we are also experimental. When we have an idea, we try it.

The ability and willingness to design experiments is a key executive capability. However, the ability to run an experiment is a key organisational capability. There’s loads of creative executives out there but their own organizations are badly designed. At CS, we have been building up processes that support experimentation for six years.

During the crisis, what else did we have going for us? We had good cadence for our communications (weekly all-hands, daily updates). We had our value system that we knew would guide us. Importantly, we also had each other.

Large parts of the group at CS have been together for a long time. We have passed through many crises together and supported each other in times of loss. We also have strong realignment processes. This creates what we call ‘organisational telepathy’. Telepathy comes from having shared mental models, shared values, and a way to keep in sync.

We also have a big network. Resilient organisations, like people, have internal resources they can draw on. They also have external resources, their network, from which they can also draw. We have always been a nice company. We share. We tell jokes. We help. This means, when the moment came, we could (and we did) ask for help.

Finally, we were lucky. We were dealt a hand. We played the hand.

Epilogue

On the 17th of July, 20 weeks after the first all-hands meeting of the crisis, I took the company over all that we had done. As we neared the end of the meeting, I started to summarise our achievements.

‘We said we’d have no redundancies and we have had no redundancies’, I said.

As I finished, with my voice breaking, and tears in my eyes, it dawned on me and everyone else on the call: we’d done it.

Previous article

Previous article