This series of three blog posts will give readers an overview on why the Raft consensus algorithm is relevant and summarizes the functionality that makes it work. The 3 posts are divided as follows:

- Part 1/3: Introduction to the problem of consensus, why it matters (even to non-PhDs), how the specification of the Raft algorithm is an important contribution to the field and a peek at the actual real-world uses of consensus algorithms.

- Part 2/3: Overview over the core mechanics that constitute the Raft algorithm itself

- Part 3/3: Why the algorithm works even on edge cases, with an overview of the algorithm's safety and liveness properties. This is then followed by the conclusion on the insights gained from looking at the Raft protocol.

Introduction

In 1985, researchers Fischer, Lynch, and Patterson (FLP) put to rest a long-standing question. Consensus in an asynchronous system with faulty processes is impossible. This may sound like an absurd result: After all, we rely on systems that rely on consensus for our everyday computing. Even websites like Facebook and Twitter require a meaningful solution to consensus in order to provide distributed solutions to implement their distributed architectures that are required for high availability.

To say that consensus is impossible, under these circumstances, may then sound like an interesting theoretical result and nothing more. However, practical solutions to this problem, that take into account the FLP result, are one of the core areas of research in distributed computing. These solutions generally work under the same framework, wherein consensus is defined strictly as the assurance of the following three properties in a distributed system:

- Validity: any value decided upon must be proposed by one of the processes

- Agreement: all non-faulty processes must agree on the same value,

- Termination: all non-faulty nodes eventually decide.

This post will discuss one solution to the consensus problem called Raft. Raft is a solution to the consensus problem that is focused on understandability and implementability

Motivation

There are many reasons why modern computing infrastructure is becoming more and more distributed.

First of all, CPU clock speeds are barely increasing today and generally there is a limit to what a single machine can handle. With companies handling higher and higher volumes of data and traffic, this forces them to use parallelism to handle these increasingly huge workloads, giving them scalability. Ever-increasing quantities and complexity of data, as well as increased speed at which it is changing, will only further this trend, fueled by the inherent financial value of large data sets and continuous technological advances.

Generally, services today are expected to be highly available, even under varying loads and despite partial system failure. Downtime has become unacceptable, be it due to maintenance or outages. This kind of resilience is only achievable through replication, the use of multiple redundant machines: When one fails or is overloaded, another one can take over the given role. To provide resilience against data-loss, data will have to be stored, as well as updated coherently across all replicated machines.

Additionally, with services having global coverage, one might want to reduce latency, having requests served by a replicated instance that is closest geographically.

In most applications, three or (many) more replicated servers are used and needed to provide optimal dynamic scalability, resilient data-storage through data replication, and low latency for optimal quality and guarantees of service. In order for a computation to give sensible results in a distributed system, it has to be executed deterministically. In a distributed system this is easier said than done.

How do you make sure that any two machines will have the same state at any given time? With the assumption of arbitrary network delays and possible temporary partitions of the network this is actually fundamentally impossible. Different weaker guarantees are possible at varying trade-offs, but the most simple possible functional guarantee is to have replicas be eventually consistent with each other, meaning that without new writes all replicas will eventually return the same value.

In order to understand deterministic execution in a distributed computation, one has to distinguish between operations that don’t interfere with each other like simple read operations and the ones that do, like write operations on the same variable. The servers performing conflicting operations need to have some way to agree on a common reality, that is to find consensus.

Most distributed are built on top of consensus: Fault-tolerant replicated state machines, data stores, distributed databases, and group membership systems are all dependent on a solution to consensus. Actually, even another fundamental problem within distributed systems, that of atomic broadcast, turns out to be fundamentally the same problem – that is isomorphic – to consensus.

To summarize, consensus is a fundamental general-purpose abstraction used in distributed systems: It gives the useful guarantee of getting all the participating servers to agree on something, as long as a certain number of failures is not exceeded. Fundamentally, the goal of consensus is not that of the negotiation of an optimal value of some kind, but just the collective agreement on some value that was previously proposed by one of the participating servers in that round of the consensus algorithm. With the help of consensus the distributed system is made to act as though it were a single entity.

Main Contribution

Raft was designed in reaction to issues with understanding and implementing the canonical Paxos algorithm: Paxos has been considered for many years the defining algorithm for solving the consensus problem and found in many real-world systems in some form or another. Yet, Paxos is considered by many to be a subtle, complex algorithm that is famously difficult to fully grasp. Additionally, the implementation of Paxos in real-world systems has brought on many challenges, problems that are not taken into account by the underlying theoretical model of Paxos.

With understandability and implementability as a primary goal, while not compromising on correctness or efficiency relative to (Multi-)Paxos, Ongaro and Ousterhout have developed the Raft protocol. Raft is a new protocol that is based on insights from various previous consensus algorithms and their actual implementations. It recombines and reduces the ideas to the essential, in order to get a fully functional protocol without compromises that is still more optimal relative to previous algorithms for consensus that do not have understandability and implementability as a primary goal.

Regarding understandability, the authors of Raft mainly critique the unnecessary mental overhead created by Paxos and propose that the same guarantees and efficiency can be obtained by an algorithm that also gives better understandability. To this end, they propose the following techniques to improve understandability: Decomposition – the separation of functional components like leader election, log replication, and safety – and state space reduction – the reduction of possible states of the protocol to a minimal functional subset.

Furthermore, the authors point out that the theoretically proven Paxos does not lend itself well to implementation: The needs of real-world systems let the actually implemented algorithm deviate so far from the theoretical description that the theoretical proof may often not apply in practice anymore. These issues are well described within Paxos Made Live – An Engineering Perspective by Chandra et. al 2007 where they describe their experiences of implementing Paxos within Chubby (which Google uses within Google File System, BigTable, and MapReduce to synchronize accesses to shared resources):

While Paxos can be described with a page of pseudo-code, our complete implementation contains several thousand lines of C++ code. The blow-up is not due simply to the fact that we used C++ instead of pseudo notation, nor because our code style may have been verbose. Converting the algorithm into a practical, production-ready system involved implementing many features and optimizations – some published in the literature and some not.

and

While the core Paxos algorithm is well-described, implementing a fault-tolerant log based on it is a non-trivial endeavor.

The poor implementability of the Paxos protocol is something that they improve upon through formulating not purely the consensus module itself, but by embedding this module within the usual use case of replicated state machines and formally proving safety and liveness guarantees over this whole real-world use case.

Consensus in the Wild

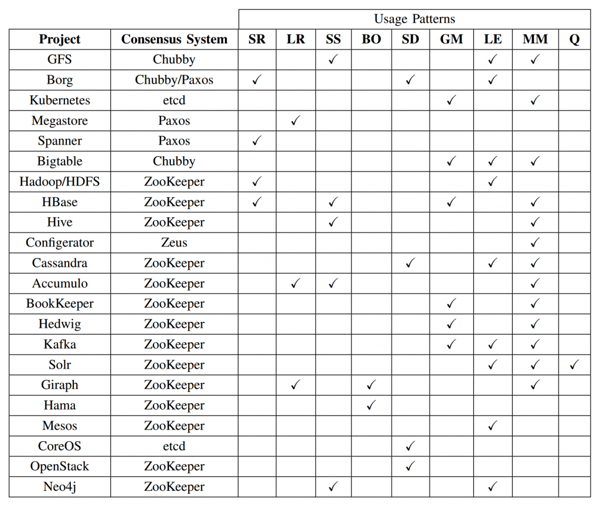

In order to give an idea how central consensus is to modern distributed systems and in which places it is used (and maybe not commonly known about), I will refer to a formal comparison between the actual consensus implementations in use within various popular frameworks Consensus in the Cloud: Paxos Systems Demystified (Ailijiang, Charapko, & Dermibas, 2016) and include their overview diagram (figure 4 in the paper):

The acronyms under usage patterns stand for server replication (SR), log replication (LR), synchronisation service (SS), barrier orchestration (BO), service discovery (SD), leader election (LE), metadata management (MM), and Message Queues (Q).

The consensus system of Chubby is based on Multi-Paxos (a variation on Paxos that decides on more than a single value), Zookeeper is based on Zab (a protocol similar but not the same as Paxos), and etcd is built on top of Raft – the protocol about which this blog post speaks.

Another two good examples of the Raft protocol in practice are Consul and Nomad from Hashicorp. Consul is a "consensus system" in the language of the above table and is widely used for service discovery in distributed systems. Nomad – Hashicorp's orchestration platform – uses Raft for state machine replication and integrates with Consul for service discovery of scheduled workloads. A comparsion of Consul with some of the other consensus systems in the above table can be found here: https://www.consul.io/intro/vs/zookeeper.html.

Continue with Part 2/3: Overview over the core mechanics that constitute the Raft algorithm itself

References

In search of an understandable consensus algorithm. Ongaro, Diego, & Ousterhout (2014) USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 14).

ARC: analysis of Raft consensus. Howard (2014). Technical Report UCAM-CL-TR-857.

Consensus in the Cloud: Paxos Systems Demystified Ailijiang, Charapko, & Demirbas (2016). The 25th International Conference on Computer Communication and Networks (ICCCN).

Paxos made live: an engineering perspective. Chandra, Griesemer, & Redstone (2007). Proceedings of the twenty-sixth annual ACM symposium on Principles of distributed computing.

Official overview website of materials on and implementations of Raft

Video lecture on Raft: https://youtu.be/YbZ3zDzDnrw

Figures

The overview diagram was taken from Consensus in the Cloud: Paxos Systems Demystified (Ailijiang, Charapko, & Dermibas, 2016) and is figure 4 in the paper.

Previous article

Previous article