Imagine a business that knows its survival depends on change—but can't decide how to act. This scenario plays out more often than you'd think, with fear of failure paralysing decision-making and ensuring stagnation. This scenario can be summarised as a paradox:

- Fear of making the wrong decision leads to inaction.

- This is a worse decision than simply making the wrong decision.

Time and again we see organisations (and people) who appear to be uncomfortable, resistant, and plain unwilling to make the changes necessary for their business's survival.

Why Action is Important - Mode A vs Mode B

Clients rarely come to us when everything is going smoothly. Instead, they seek help when they sense a looming challenge or existential threat. The root of the problem often lies in a shift from one operating mode to another:

- Mode A: A successful, established way of working.

- Mode B: A new approach required to address a critical threat.

Mode A often brought these organizations success—enough to afford hiring us. But the degree to which Mode A remains effective varies. Some leaders recognise future challenges early and take action proactively. Others are forced to act when the threat becomes unavoidable.

Comfort Zones vs Innovation

The Product Comfort Zone

By the time we arrive, Mode A is usually a mature system—a predictable routine that delivers results within well-defined constraints. Consider a B2B software company that thrives on bespoke projects tailored to keep clients happy. This model worked for years, but now a shift toward standardized, product-based solutions threatens their dominance.

The mindset required to move from the comfort of predictable projects to the chaos of experimentation is daunting. Embracing "best practices" in product development and maintenance often means stepping into uncertainty—where failure is a prerequisite for growth. This mindset shift is central to the "project to product" movement.

The Over-Planning Comfort Zone

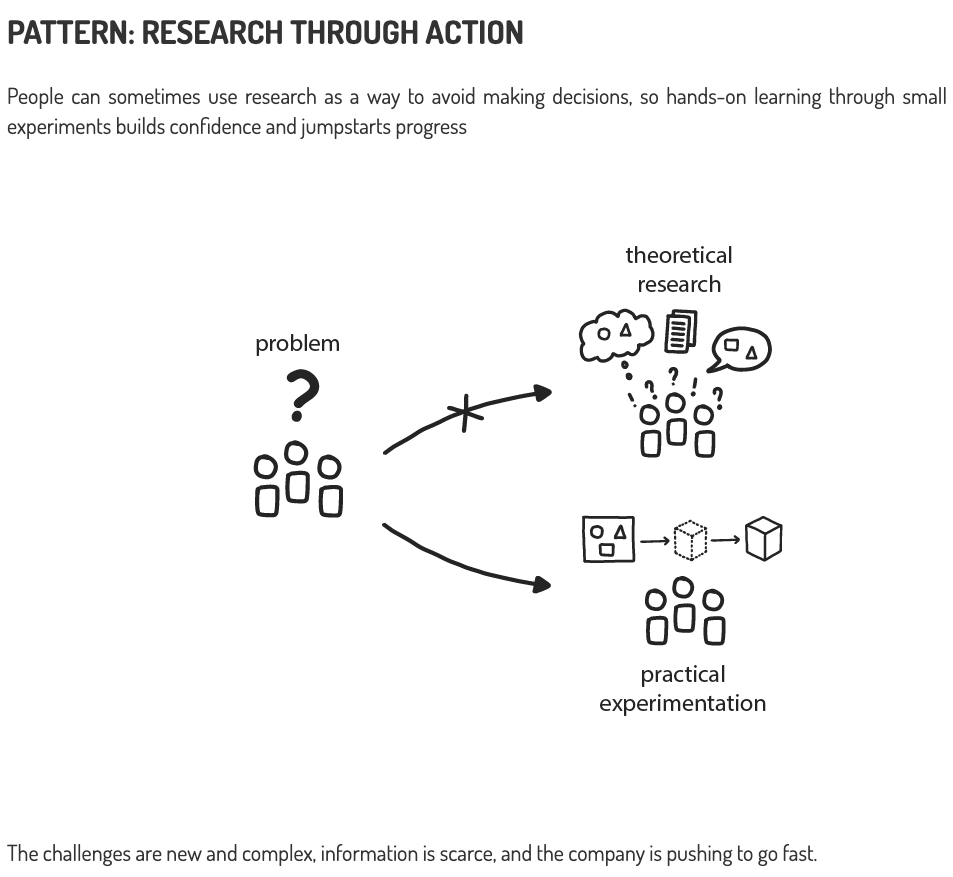

Another common barrier is over-planning. Some organizations resist acting without certainty about outcomes. For instance, a manufacturing client debated a technical challenge for years, unwilling to launch a project without assurance of success. Their culture of "getting it right the first time" clashed with the iterative experimentation common in software development.

In other words, they were incapable of researching through action.

Cloud Native Pattern: Research through action.

We argued that they should embrace that uncertainty and run a time-boxed six-week project to learn whether the project was possible by working with their architects to prove or disprove as many approaches as possible. Despite having spent considerable resources (and therefore money) over the years pondering the problem, they found it very difficult to spend money to learn (a key aspect of becoming a learning organisation). The project succeeded in creating a proof of concept, and we helped them productionise the solution.

Cloud Native Pattern: Learning Organisation

Cloud Native Pattern: Learning Organisation

Mistakes As A Path to Growth

Many of our clients object strongly when we say to them that they should embrace risk-taking and potential failure. There are two main reasons for this.

- Fear of past consequences

- Misplaced expectations

The first is that they tell us they've been punished in the past for making mistakes. This is a classic pattern of Mode A, where businesses have found a local optimum around which they seek to operate in the most efficient way possible.

The second reason to avoid risk-taking and failure we hear from clients is that it is our fault: we 'should know the answer!'. This is the curse of the consultant: to be cast as either the impossible-to-live-up-to hero that knows everything, or the charlatan that pretends to. In a way, we do know the answers, but they're not the answers the client wants to hear. They typically want a simple (usually technical) set of instructions that means that their business changes as little as possible.

Clients often think they want a Taxi Driver...

Clients often think they want a Taxi Driver...

One way to look at this is that they want an 'taxi' driver to take them to their destination, but the reality is that we are more like 'explorers' who can help them get to their destination quicker because we have undertaken similar journeys before, but not without risk and travail.

Their particular domain and context is always unique, and they need to navigate it themselves so they learn the lessons of exploring the search space of all possibilities without getting eaten by sharks. We can advise them not to try to get the next island without a robust ship, or to avoid the sounds of lions in the distance, but we don't know which particular set of actions will work in their specific circumstances in advance.

...but what they actually need is an experienced explorer

...but what they actually need is an experienced explorer

It's often useful to note that history teaches us that those with experience of making change quickly are not afraid to make mistakes. Whatever you think of Elon Musk, it's undeniable that he's led businesses through times of crisis requiring fast innovation. When talking about process improvements, he's said that 'if you are not occasionally adding things back in, you are not deleting enough'. In other words, in order to find a new local optimum in business processes, you need to take risks to make changes fast enough. A very senior manager once told me that 30% of his contributions to meetings were 'probably wrong'. I was taken aback by this revelation (he was a very smart person, and in my experience rarely wrong). However, he had essentially the same impulse as Elon Musk: in order to make change happen he had to take risks and provocative to quickly surface the reality.

Of course, there are limits to the risks a business should take. So what risks are reasonable to make, and what aren't? Jeff Bezos has a very useful heuristic for determining this. He divides decisions into two categories: 'one-way door' vs 'two-way door' decisions. A one-way door represents a decision that, once taken, can't be easily reversed. A two-way door decision is reversible.

If a decision is a 'two-way' door decision, then making that decision should not require much deliberation: if it doesn't work, you reverse the decision and move on. A major strategic decision to change your company from 'project to product', for example, is a one-way door decision: reversing it would be very costly. So it's worth spending time and effort on before you decide to pursue it. Once you decide, however, most decisions that follow are two-way door decisions.

An interesting aspect of spending time with companies that have chosen to make a strategic change is that they find themselves paralysed by indecision, and in their discussions explicitly or implicitly second-guess the one-way decision while deliberating on the two-way decision.

This can happen in several related ways:

-

Looking for reasons not to take the obvious next step, because of uncertainty about what might follow that next step

-

Revisiting the original decision (for which they are usually not responsible)

-

Fearing (and discussing at length) any negative consqeuences that may need to be dealt with as a result

Decision-Making and Overcoming Paralysis

Cynefin is a useful conception framework we've written about before that can help explain this to people struggling with this indecision. I won't repeat what I've said in the linked article, but briefly recapitulate here.

When a decision-making context is well-known (ie operating with varying degrees of efficiency around a local optimum), then the best way to manage this is analyse before acting. The domain and context is well-known, so you can predict with some certainty the consequences of your actions. Therefore, the benefits of analysis outweighs the cost. An example of this from everyday life might be planning a weekly grocery shop. You know what meals you typically prepare, have a good idea of the ingredients you need, and can reasonably estimate costs and quantities. Spending time analysing your meal plan and food inventory helps ensure efficiency, reduces waste, and optimises your budget. The context is predictable, and careful planning leads to the best outcomes.

When a decision-making context is not well-known (ie you are probing a wider search space to find a new optimum), then the best way to manage this is to act before analysing. An example of this from everyday life might be trying out a new fitness routine. You may not know in advance which exercises or schedule will work best for your goals, preferences, and constraints. Instead of spending excessive time researching and planning, you start by experimenting—perhaps trying a yoga class, a gym session, or a running schedule. As you observe what you enjoy, what fits your lifestyle, and what yields results, you can refine your approach. This process of acting, learning, and adapting helps you discover a new "local optimum" in an unknown space.

There's a nice story from Richard Feynman about effective decision-making in an uncertain world. He describes working at Los Alamos, where a Colonel had given an order that only the physicists know about the physics. Everyone else must be kept in the dark about why they were moving chemicals around for fear of them learning nuclear secrets. Feynman disagreed with this because he thought safety might be compromised if these people didn't understand the consequences.

I said, “In my opinion it is impossible for them to obey a bunch of rules unless they understand how it works. It’s my opinion that it’s only going to work if I tell them, and Los Alamos cannot accept the responsibility for the safety of the Oak Ridge plant unless they are fully informed as to how it works!”

The lieutenant takes me to the colonel and repeats my remark. The colonel says, “Just five minutes,” and then he goes to the window and he stops and thinks. That’s what they’re very good at—making decisions. I thought it was very remarkable how a problem of whether or not information as to how the bomb works should be in the Oak Ridge plant had to be decided and could be decided in five minutes. So I have a great deal of respect for these military guys, because I never can decide anything very important in any length of time at all.

In five minutes he said, “All right, Mr. Feynman, go ahead.”

As Feynman implies, it would have been easy for the Colonel to defer his decision due to the uncertainty. Most plausibly, he might argue that a committee be set up to make the correct decision. But that would undermine the overall strategy of the project, which was to build a nuclear bomb as fast as possible. In the event, it's likely he determined that there were too many unknowns to make a 'correct' decision, and that the need for safety trumped the risk of secret leakage in this case.

The colonel pondered it long enough to let the facts settle in his mind, and then made a decision and carried it out immediately. We still don't know if it was the 'correct' decision (maybe secrets were leaked; maybe the safety risk was in fact far lower than Feynman thought), but that's the core of the challenge: making decisions in an uncertain context. [1]

How to Get There

It's one thing to realise that you need to develop a culture of experimentation, risk-taking, and 'bias to action', quite another to achieve it. The first thing that must happen is that the leadership must support, encourage, and coach this change. Any hint that they are not supporting this change will result in confusion and resistance at lower levels of the organisation. This must be clearly demonstrated through consistent communication, actions that align with their message, and by prioritising resources to enable experimentation and risk-taking.

Next you have to set up incentives and financial structures that support the behaviours you want. We've written about this before in the 'money flows' series, and the piece on SpaceX is particularly relevant here. Their entire financial organisation is built around encouraging innovation (rather than cost control), with the goal of 'reducing the cost per kg of sending cargo into space'.

One common pattern that we see can be effective to get organisations out of their old habits is to set up a project that exists outside the existing governance structures of the business. It doesn't have to be isolated entirely, but should have enough independence to experiment without being bogged down by the constraints of traditional approval and oversight processes. This allows it to operate with a lean and agile approach, fostering innovation while reducing the cost of experimentation.

Cloud Native Pattern: Reduce the Cost of Experimentation

Footnotes

[1] Another good example from fiction: In the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Coming of Age", Wesley Crusher undergoes the Starfleet Academy entrance exam, which includes a psychological test designed to assess his decision-making abilities under pressure. During this test, Wesley is confronted with a simulated emergency (that he believes to be real) where he must choose between rescuing one of two individuals in a perilous situation and effectively condemning one to death, evaluating his capacity to make critical decisions when outcomes are uncertain.

Previous article

Previous article