Recently an Amazon Prime Video (APV) article about their move from serverless tools to ECS and EC2 did the rounds on all the tech socials. A lot of noise was made about it, initially because it was interpreted as a harbinger of the death of serverless technologies, followed by a second wave that lashed back against that narrative. This second wave argued that what had happened was not a failure of serverless, but rather a standard architectural evolution of an initial serverless microservices implementation to a ‘microservice refactoring’.

This brouhaha got me thinking about why, as an architect, I’ve never truly got onto the serverless boat, and what light this mini-drama throws on that stance. I ended up realising how Amazon and AWS had been at the centre of two computing revolutions that changed the computing paradigm we labour within.

Before I get to that, let’s recap the story so far.

The Story

The APV team had a service which monitored every stream viewed on the platform, and triggered a process to correct poorly-operating streams. This service was built using AWS’s serverless Step Functions and Lambda services, and was never intended to run at high scale.

As the service scaled, two problems were hit which together forced a re-architecture. Account limits were hit on the number of AWS Step Function transitions, and the cost of running the service was prohibitive.

In the article’s own words: ‘The move from a distributed microservices architecture to a monolith application helped achieve higher scale, resilience, and reduce costs. [...] We realised that [a] distributed approach wasn’t bringing a lot of benefits in our specific use case, so we packed all of the components into a single process.’

The Reactions

There were more than a few commentators who relished the chance to herald this as the return of the monolith and/or the demise of the microservice. The New Stack led with an emotive ‘Amazon Dumps Microservices’ headline, while David Heinemeier Hansson, as usual, went for the jugular with ‘Even Amazon Can’t Make Sense of Serverless or Microservices’.

After this initial wave of ‘I told you so’ responses, a rearguard action was fought by defenders of serverless approaches to argue that reports of the death of the serverless and microservices was premature, and that others were misinterpreting the significance of the original article.

Adrian Cockroft, former AWS VP and well-known proponent of microservices fired back with ‘So Many Bad Takes - What Is There To Learn From The Prime Video Microservices To Monolith Story’, which argued that the original article did not describe a move from microservice to monolith, rather it was ‘clearly a microservice refactoring step’, and that the team’s evolution from serverless to microservice was a standard architectural pathway called ‘Serverless First’. In other words: nothing to see here, ‘the result isn’t a monolith’.

The Semantics

At this point, the debate has become a matter of semantics: What is a microservice? Looking at various definitions available, the essential unarguable point is that a microservice is ‘owned by a small team’. You can’t have a microservice that requires extensive coordination between teams to build or deploy.

But that can’t be the whole story, as you probably wouldn’t describe a small team that releases a single binary with an embedded database, a web server and a Ruby-on-Rails application as a microservice. A microservice implies that services are ‘fine-grained […] communicating through lightweight protocols’.

If a microservice is 'fine-grained', then there must be some element of component decomposition in a set of microservices that make up a set of applications. So what is a component? In the Amazon Prime Video case, you could argue both ways. You could say that the tool itself is a component, as it is a bounded piece of software managed by a small team, or you could say that the detectors and converters within the tool are separate components mushed into a now-monolithic application. You could even say that my imagined Ruby-on-Rails monolithic binary above is a microservice if you want to just define a component as something owned by a small team.

And what is an application? A service? A process? And on and on it goes. We can continue deconstructing terms all the way down the stack, and as we do so, we see that whether or not a piece of software is architecturally monolithic or a microservice is more or less a matter of perspective. My idea of a microservice can be the same as your idea of a monolith.

But does all this argumentation over words matter? Maybe not. Let’s ignore the question of what exactly a microservice or a monolith is for now (aside from ‘small team size’) and focus on another aspect of the story.

Easier to Scale?

The second paragraph of AWS’s definition of microservices made me raise my eyebrows:

‘Microservices architectures make applications easier to scale and faster to develop, enabling innovation and accelerating time-to-market for new features.’

Source: https://aws.amazon.com/microservices/

Regardless of what microservices were, these were their promised benefits: faster to develop, and easier to scale. What makes the AVP story so triggering to those of us who had been told we were dinosaurs is that the original serverless implementation of their tool was ludicrously un-scalable:

We designed our initial solution as a distributed system using serverless components (for example, AWS Step Functions or AWS Lambda), which was a good choice for building the service quickly. In theory, this would allow us to scale each service component independently. However, the way we used some components caused us to hit a hard scaling limit at around 5% of the expected load.

Source: https://www.primevideotech.com/video-streaming/scaling-up-the-prime-video-audio-video-monitoring-service-and-reducing-costs-by-90

and not just technically un-scalable, but financially too:

Also, the overall cost of all the building blocks was too high to accept the solution at a large scale.

To me, this doesn’t sound like their approach has made it ‘easier to scale’.

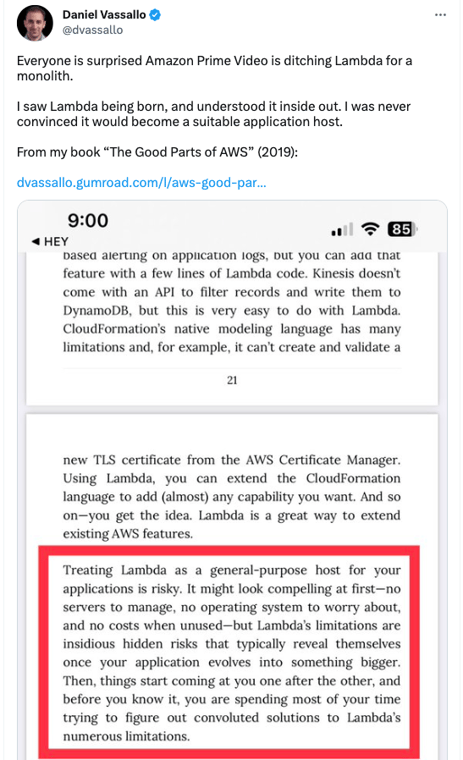

Some, indeed, saw this coming:

Faster to Develop?

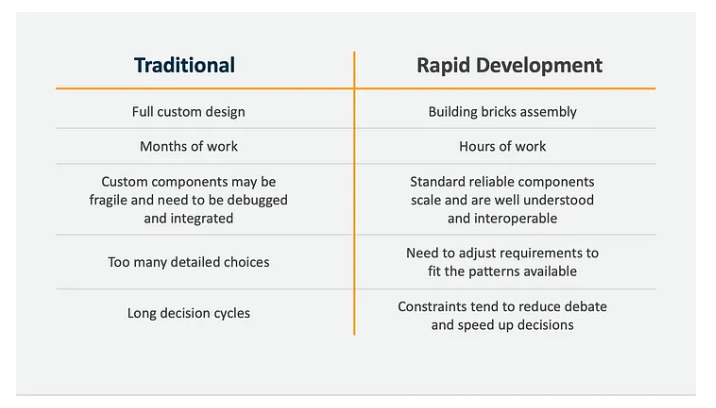

But what about the other benefit, that of being ‘faster to develop’? Adrian Cockroft’s post talks about this, and lays out this comparison table:

This is where I must protest, starting with the second line, which states that ‘traditional’, non-serverless/non-microservices development takes ‘months of work’ compared to the ‘hours of work’ microservices applications take to build.

Anyone who has actually built a serverless system in a real world context will know that it is not always, or even usually, ‘hours of work’. To take one small example of problems that can come up:

...to which you might add: difficulty of debugging, integration with other services, difficulty of testing scaling scenarios, state management, getting IAM rules right… the list goes on.

You might object to this, and argue that if your business has approved all the cloud provider’s services, and has a standard pattern for deploying them, and your staff is already well versed in the technologies and how to implement them, then yes, you can implement something in a few hours.

But this is where I’m baffled. In an analogous context, I have set up ‘traditional’ three-tier systems in a minimal and scalable way in a similar time-frame. Much of my career has been spent doing just that, and I still do that in my spare time because it’s easier for me for prototyping to do just that on a server than wiring together different cloud services.

The supposed development time difference between the two methods is not based on the technology itself, but the context in which you’re deploying it. The argument made by the table is tendentious. It’s based on comparing the worst case for ‘traditional’ application development (months of work) with the best case for ‘rapid development’ (hours of work). Similar arguments can be made for all the table’s comparisons.

The Water We Swim In

Context is everything in these debates. As all the experts point out, there is no architectural magic bullet that fits all use cases. Context is as complex as human existence itself, but here I want to focus on two areas specifically:

- governance

- knowledge

The governance context is the set of constraints on your freedom to build and deploy software. In a low-regulation startup these constraints are close to zero. The knowledge context is the degree to which you and your colleagues know how a set of technologies work. It’s assumptions around these contexts that make up the fault lines of most of the serverless debate.

Take this tweet from AWS, which approvingly quotes the CEO of Serverless:

"The great thing about serverless is that you don't have to think about migrating a big app or building out this huge application, you just have to think about one task, one unit of work." - @austencollins, Founder & CEO @goserverless w/@danilop. https://t.co/TVfP1CFCNS pic.twitter.com/yCuY8ChvmM

— Amazon Web Services (@awscloud) January 30, 2020

The great thing about serverless is that you don't have to think about migrating a big app or building out this huge application, you just have to think about one task, one unit of work.

@austencollins, Founder & CEO @goserverless

I can’t speak for other developers, but that’s almost always true for me most of the time when I write functions (or procedures) in ‘traditional’ codebases. When I’m doing that, I’m not thinking about IAM rules, how to connect to databases, the big app, the huge application. I’m just thinking about this one task, this unit of work. And conversely, if I’m working on a serverless application, I might have to think about all the problems I might run into that I listed above, starting with database connectivity.

You might object that a badly-written three-tier system makes it difficult to write such functions in isolation because of badly-structured monolithic codebases. Maybe so. But microservices architectures can be bad too, and let you ‘think about the one task’ you are doing when you should be thinking about the overall architecture. Maybe your one serverless task is going to cost a ludicrous amount of money (as with APV), or is duplicated elsewhere, or is going to bottleneck another task elsewhere.

Again: The supposed difference between the two methods is not based on the technology itself, but the context in which you’re working. If I’m fully bought into AWS as my platform from a governance and knowledge perspective, then serverless does allow me to focus on just the task I’m doing, because everything else is taken care of by the business around me. Note that this context is independent of 'the problem you are trying to solve'. That problem may or may not lend itself to a serverless architecture, but is not the context in which you're working.

Here I’d like to bring up a David Foster Wallace parable about fish:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”

When you’re developing, you want your context to be like water to a fish: invisible, not in your way, sustaining you. But if I’m not a fish swimming in AWS’s metaphorical water, then I’m likely to splash around a lot if I dive into it.

Most advocates of serverless take it as a base assumption of the discussion that you are fully, maturely, and exclusively bought into cloud technologies, and the hyperscalers’ ecosystems. But for many more people working in software (including our customers), that’s not true, and they are wrestling with what, for them, is still a relatively unfamiliar environment.

A Confession

I want to make a confession. Based on what you’ve read so far, you might surmise I’m someone who doesn’t like the idea of serverless technology. But I’ve spent 23 years so far doing serverless work. Yes, I’m one of those people who claims to have 23 years experience in a 15-year old technology.

In fact, there’s many of us out there. This is because in those days we didn’t call these technologies ‘serverless’ or ‘Lambda’, we called them ‘stored procedures’.

https://twitter.com/ianmiell/status/921767022056345602

Serverless seems like stored procedures to me. The surrounding platform is just a cloud mainframe rather than a database.

— Ian Miell (@ianmiell) October 21, 2017

I worked for a company for 15 of those years where the ‘big iron’ database was the water we swam in. We used it for message queues (at such a scale that IBM had to do some pretty nifty work to optimise for our specific use case and give us our own binaries off the main trunk), for our event-driven architectures (using triggers), and as our serverless platform (using stored procedures).

The joy of having a database as the platform was exactly the same then as the joys of having a serverless platform on a hyperscaler now. We didn’t have to provision compute resources for it (DBA’s problem), maintain the operating system (DBA’s problem), or worry or performance (DBA’s problem, mostly). We didn’t have to think about building a huge application, we just had to think about one task, one unit of work. And it took minutes to deploy.

People have drawn similar analogies between serverless and xinetd.

xinetd, but the daemons are containers. Not a bad idea, but certainly not the solution to everything, which is how some "serverless experts" seem to be approaching this.

— Timothy Van Heest (@turtlemonvh) September 5, 2019

Serverless itself is nothing new. It’s just a name for what you’re doing when you can write code and let someone else manage the runtime environment (the ‘water’) for you. What’s new is the platform you treat as your water. For me 23 years ago, it was the database. Now it’s the cloud platform.

Mainframes, Clouds, Databases, and Lock-In

The other objection to serverless that’s often heard is that it increases your lock-in to the hyperscaler, something that many architects, CIOs, and regulators say they are concerned about. But as a colleague once quipped to me: “Lock-in? We are all locked into x86”, the point being that we’re all swimming in some kind of water, so it’s not about avoiding lock-in, but rather choosing your lock-in wisely.

It was symbolic when Amazon (not AWS) got rid of their last Oracle database in 2019, replacing them with AWS database services. In retrospect, this might be considered the point where businesses started to accept that their core platform had moved from a database to a cloud service provider. A similar inflection point where the mainframe platform was supplanted by commodity servers and PCs might be considered to be July 5, 1994, when Amazon itself was founded. Ironically, then, Amazon heralded both the death of the mainframe, and the birth of its replacement with AWS.

The Circle of Life

With this context in mind, it seems that the reason I never hopped onto the serverless train is because, to me, it’s not the software paradigm I was ushered into as a youngengineer. To me, quickly spinning up a three-tier application is as natural as throwing together an application using S3, DynamoDB, and API Gateway is for those cloud natives that cut their teeth knowing nothing else.

What strikes this old codger most about the Amazon Prime Video article is the sheer irony of serverless’s defenders saying that its lack of scalability is the reason you need to move to a more monolithic architecture. It was serverless’s very scalability and the avoidance of the need to re-architect later that was one of its key original selling points!

But when three-tier architectures started becoming popular I’m sure mainframers of the past said the same thing: “What’s the point of building software on commodity hardware, when it’ll end up on the mainframe?” Maybe they even leapt on articles describing how big businesses were moving their software back to the mainframe, having failed to make commodity servers work for them, and joyously proclaimed that rumours of the death of the mainframe was greatly exaggerated.

And in a way, maybe they were right. Amazon killed the physical mainframe, then killed the database mainframe, then created the cloud mainframe. Long live the monolith!

If you want to read more about what makes a Cloud Native work for organisations like yours, download the Cloud Native Attitude book below.

.png?width=2000&height=400&name=1%20(1).png)

Previous article

Previous article