Previously, I wrote about how a software company’s cultural challenges can be traced back to how money flows through it, using the example of an ‘accidental product’ B2B type of business that tries to go from project to product.

In this article, I want to extend that ‘cultural economics’ thinking to the subject of Agility.

An agile anecdote

Around 2005, when calling a team agile was the new fashion (and few really knew what it meant) I worked for a company that delivered software to the sports betting industry. The industry is notoriously unregulated and cut-throat, and its combatants were (and probably still are) in a constant arms race to outdo each other for new features to attract and keep its non-sticky customers.

The pressure to deliver fast is exacerbated by another factor: major events don’t move. If you have a great new soccer bet type it needs to be ready for the World Cup, where a huge number of bets will be placed. Afterwards though, it’s effectively commercially worthless. So if a feature isn’t quite ready, even if it’s slightly flawed, you rush it out and try to deal with the fallout later.

In this context, we had a job to do for a client by a deadline and didn’t have the staff to do it. Skills in this area were rare but we found a company ready and seemingly able to do the work. When we sat down with them, they told us they liked to work ‘in an agile way’. We didn’t really know what they meant by this, but ploughed ahead anyway. We were desperate.

We soon hit a big problem. They ended their first sprint, and said they would have to re-evaluate the timelines as they had, in true agile fashion, reflected on their experience and decided it would take longer to deliver than they thought. We explained there was an immovable deadline, and that this was a non-negotiable constraint. They said they were sorry, but they were agile, so that was the deal.

We fired them pretty quickly, and managed to do the work in-house. We made a few glib remarks about their lack of agility about their agile approach and moved on.

Does being agile even make sense?

Reflecting on this war story the other week while thinking about a consulting client’s challenges, I was prompted to ask whether aiming for true agility is the right thing.

In software now it can feel like an unquestionable dogma that being agile is always good, but it’s worth highlighting the situations in which trying to be agile is like fitting a square peg in a round hole.

Before we do that, I want to outline what I think the ideal conditions for agility are, and then we can talk about the common conditions for not being agile.

What is Agility?

I don’t really want to get into a theological discussion of what agility truly is, so I’m going to refer to the original Manifesto only rather than any of its descendants, and here just emphasise the part that says ‘Responding to change over following a plan’Conditions for agility

The Agile Manifesto’s original themes emphasise internal team agency over external demands.

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

Working software over comprehensive documentation

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

Responding to change over following a plan

Each of the points ‘valued more’ on the left are those that favour team autonomy. The team gets to decide when the thing gets built, how it gets built, and even what the thing they’re building consists of. Because the customer can’t be ignored, they are brought into the team rather than faced down over a contract.

The conditions required for team autonomy, and therefore for agile, can be summed up in one word: trust.

All the values prized in the Agile Manifesto require trust to be nurtured and sustained.

In low-trust environments:

- Process and tools are centrally mandated

- Documentation is centrally mandated

- Collaboration is low – demands are made of teams in a transactional fashion

- Plans are king. Deviation from The Plan is always a problem rather than a response.

In high-trust environments, all these aspects of building are decided within the team.

Behind this trust must lie one of two relationships between the builders and those who ultimately provide the money (ie the customer). Either:

- The customer is embedded within the team, or

- The customer has only an indirect voice on the team’s performance

Implicit in this is a trust model between patron and producer where there are no hard commitments to delivery.

Back to the iron triangle

So far we’ve related agility to trusting the delivery team to deliver, and this means the customer has to accept that when, how and what will be delivered will change during the project. In other words, the team makes no binding commitment to delivery.

Customers might accept this in two situations: where they are directly involved in this dynamic decision-making, or if the nature of the commitment made to them does not determine what is delivered to them. For example, if Netflix don’t deliver a ‘favourites’ feature on their SmartTV interface by February I can’t sue them – I just stop paying them. It’s up to them what they deliver to me, and up to me whether I pay them.

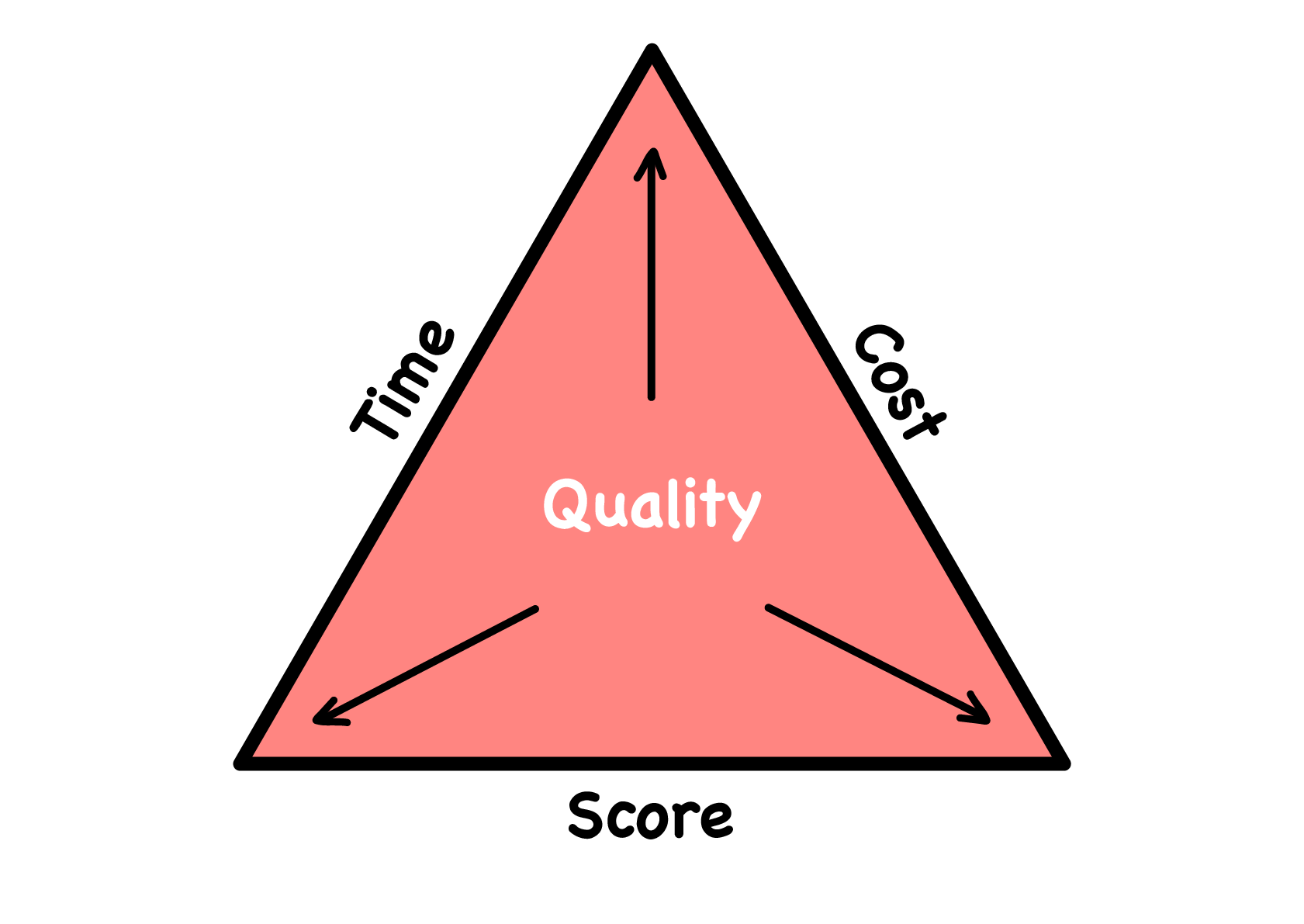

Either way, the nature of the commitment made to the patron is central to whether agility is possible. And when we talk about commitments in projects, we talk about the iron triangle. This old project management approach delineates the areas that one can make commitments to in a project. In other words, these are the things that are usually in contracts: when (time), what (scope), and cost. All other things being equal, changing the size of any of these areas will affect the quality of the delivery.

This old project management approach delineates the areas that one can make commitments to in a project. In other words, these are the things that are usually in contracts: when (time), what (scope), and cost. All other things being equal, changing the size of any of these areas will affect the quality of the delivery.

Is there a contract behind your work?

The first question you must ask yourself when thinking about whether it makes sense to try to be agile is to ask whether, at the root of your efforts, is a binding commitment to deliver on those three points to whoever is ultimately funding you?

Flowing from this question will be all the behaviours that work against the potentially innovative product or original thinking that agility exists to enable:

- ‘You can’t take longer to deliver this, so you will have to make choices that affect the quality of the delivery.’

- ‘You can’t reduce the scope delivered in the time, you will have to make choices.’

- ‘We can’t add more resources to deliver the project (even if that would help), because this would make it unprofitable.’

- ‘We have to coordinate everyone to deliver a specific thing at a specific time, so we need to plan ahead in a waterfall way (though we may call it agile).’

Binding contracts also prevent the slack that all creative or innovative teams require to work for the longer-term interests of the producing business.

Are you mining, or prospecting?

Another way to look at this question of whether it makes sense to be agile is to consider whether your work is ultimately thought of as ‘mining’ or ‘prospecting’.

When you mine, you’ve found the value in the ground, and you know how to extract it. The task is therefore simple:

- Get the value out of the ground

- Do it as cheaply as possible

When you prospect, you don’t know where the value is, so you have to find it as efficiently as possible. So you have to:

- Decide where to start looking

- Search in that area

- Reflect on what you’ve found

- Decide where to look next, or start mining

This is agility in a nutshell – we have some expertise, but we don’t know all the answers, so we will have to prospect for value. We may discover new things along the way and change the outcome through innovative reflection on what we learn as we go. We can’t make commitments: we may strike gold, or nothing at all.

Implicit in a fixed contract is that the work you are doing is ‘mining’. You’ve promised to get the value out. Whether you destroy your tooling doing it, or exhaust your miners, or break laws is not (formally) the concern of the patron. You’ve committed to deliver the value, and how to do it is your problem.

So legal contracts are the problem?

Bear in mind that the fact of whether a formal signed contract exists is not the sole determinant of whether a commitment made prevents you from being agile. Many organisations issue contracts, but their relationship is such that the contracts only exist as an insurance in case the existing trust between teams completely breaks down. Commitments can be renegotiated because both sides trust each other, and find a way to satisfy each other's needs and demands.

As the old saying goes: “if you need to get the contract off the shelf, you’ve both already lost”. Once trust goes, everything falls apart.

By the same token, internal patrons within businesses may commission projects or efforts without a formal contract, but with an implicit contract that signals low trust or lack of flexibility.

Fundamentally, the question should not be ‘is there a contract?’, rather ‘is there a binding and inflexible commitment?’

If a formal contract exists that defines cost, scope, or time, there is always a danger that the patron believes such a commitment has been made. If no formal contract exists but money is changing hands, then it’s simpler: the duty of the producer is to keep the client happy enough that they keep paying, but how they do that is entirely up to them.

Trust, commitment, and contracts

When you hear exhortations to be agile at your work, think about the aspects of trust, commitment, and contracts, and how they relate to your work:

- Has a commitment been made (or does the patron believe a commitment has been made)?

- Does the patron trust the delivery team to deliver in their best interests?

- Is there a contract ‘behind’ the work?

Considering these questions can determine whether agility is a realistic approach for your working context.

The corollary of this is that if agility is what you want, you need to work on these fundamentals first to make things change. Otherwise you will be floundering against a powerful tide.

Related articles

For more on this topic we recommend the following articles:

Wardley Mapping and Agile at 20: It’s Not One-Size-Fits-All by Jennifer Riggins

Agile in the Cloud Native Era by Jamie Dobson

Previous article

Previous article