When I started my career as an engineer in the early noughties, I was very keen on developer experience (devex).

So when I joined a company whose chosen language was TCL (no, really), I decided to ask the engineering mailing list what IDEs they used. Surely the senior engineers, with all their wisdom and experience, would tell which of the many IDEs available at the time made them the most productive? This was decades before ‘developer experience’ had a name, but nonetheless it was exactly what I was talking about, and what people fretted about.

Minutes later, I received a terse one-word missive from the CTO:

From: CTO

Subject: IDEs

> Which IDEs do people recommend using here? Thanks,

> Ian

vimBeing young and full of precocious wisdom, I ignored this advice for a while. I installed Eclipse (which took up more RAM than my machine had, and quickly crashed it), and settled on Kate (do people still use Kate?). But eventually I twigged that I was no more productive than those around me that used vim.

So, dear reader, I married vim. That marriage is still going strong twenty years later, and our love is deeper than ever.

This pattern has been repeated multiple times with various tools:

- see the fancy new GUI

- try it

- gradually realise that the command-line, text-only, steep-learning-curve, low-tech approach is the most productive

Some time ago it got to the point where when someone shows me the GUI, I ask where the command-line version is, as I’d rather use that. I often get funny looks at both this, and when I say I’d rather not use Visual Studio if possible.

I also find looking at gvim makes me feel a bit queasy, like seeing your dad dancing at a wedding.

This is not a vim vs not-vim post. Vim is just one of the oldest and most enduring examples of an approach which I’ve found has served me better as I’ve got older.

I call this approach ‘low-tech devex’, or ‘LTD’. It prefers:

- Long-standing, battle-hardened tools that have stood the test of time

- Tools with stable histories

- Small tools with relatively few dependencies

- Text-based input and output

- Command-line approaches that exemplify unix principles

- Tools that don’t require daemons/engines to run

LTD also is an abbreviation of ‘limited’, which seems appropriate…

How Is Low-Tech Devex Better?

All LTD tools arguably reflect the aims and principles of the UNIX philosophy, which has been summarised as:

Write programs that do one thing and do it well. Write programs to work together. Write programs to handle text streams, because that is a universal interface.

Portability

LTD is generally very portable. If you can use vim, it will work in a variety of situations, both friendly and hostile. vim, for example can easily be run on Windows, MacOS, Linux, or even that old HPUX server which doesn’t even run bash, yet does run your mission-critical database.

Speed

These tools tend to run fast when doing their work, and take little time to start up. This can make a big difference if you are in a ‘flow’ state when coding. They also tend to offer fewer distractions as you’re working. I just started up VSCode on my M2 Mac in a random folder with one file in it, and it took over 30 seconds until I could start typing.

Power

Although the learning curve can be steep, these tools tend to allow you to do extremely powerful things. The return on the investment, after an initial dip, is steep and long-lasting. Just ask any emacs user.

Composability / Embeddability

Because these tools have fewer dependencies, they tend to be more easily composable with – or embeddable in – one another. This is a consequence of the Unix philosophy.

For example, using vim inside a running Docker container is no problem, but if you want to exec onto your Ubuntu container running in production and run VSCode quickly and easily, good luck with all that. (Admittedly, VSCode is a tool I do use occasionally, as it’s very powerful for certain use cases, very widely used, and seems designed to make engineers’ lives easier rather than collect a fee. But I do so under duress, usually.)

And because they use also typically use standard *nix conventions, these tools can be chained together to produce more and more bespoke solutions quickly and flexibly.

Users’ Needs Are Emphasised

LTD tools are generally written by and for the user’s needs, rather than any purchaser’s needs. Purchasers like fancy GUIs and point-and-click interfaces, and ‘new’ tools. Prettiness and novelty don’t help the user in the long term.

More Sustainable

These tools have been around for decades (in most cases), and are highly unlikely to go away. Once you’ve picked one for a task, it’s unlikely you’ll need a new one.

More Maintainable

Again, because these tools have been around for a long time, they tend to have a very stable interface and feature set. There’s little more annoying than picking up an old project and discovering you have to upgrade a bunch of dependencies and even rewrite code to get your project fired up again (I’m looking at you, node).

How We Use LTD

Here’s an edited example of a project I wrote for myself which mirrors some of the projects we have built for our more engineering-focussed clients.

Developer experience starts with a Makefile. Traditionally, Makefiles were used for compiling binaries efficiently and accounting for dependencies that may or may not need updating.

In the ‘modern’ world of software delivery, they can be used to provide a useful interface for the engineer for what the project can do. As the team works on the project they can add commands to the list for tasks that they often perform.

help:

@grep -E '^[a-zA-Z_-]+:.*?## .*$$' $(MAKEFILE_LIST) | sort | awk 'BEGIN {FS = ":.*?## "}; {printf "\033[36m%-30s\033[0m %s\n", $$1, $$2}'

docker_build: ## Build the docker image to run in

docker build -t data-scraper . | tee /tmp/data-scraper-docker-build

docker tag data-scraper:latest docker.io/imiell/data-scraper

get_latest: docker_build ## Get latest data

@docker run \

-w="/data-scraper" \

--user="$(shell id -u):$(shell id -g)" \

--volume="$(PWD):/data-scraper" \

--volume="$(HOME)/.local:/home/imiell/.local" \

-- volume="$(HOME)/.bash_history:/home/imiell/.bash_history" \

--volume="/etc/group:/etc/group:ro" \

--volume="/etc/passwd:/etc/passwd:ro" \

--volume="/etc/shadow:/etc/shadow:ro" \

--network="host" \

--name=get_latest_priority \

data-scraper \

./src/get-latest.sh

It's a great way of sharing 'best practice' within a team.

I then have a make.sh script which wraps calls to make with features such as capturing logs in a standard format and cleaning up any left-over files once a task is done. I then use that script in a crontab in production like this:

*/5 * * * * imiell run-one /home/imiell/git/data-scraper/src/make.sh \

get_latest

Using run-one and cron I can effectively have a daemon running on my server with very little overhead.

A challenge with make is that it has quite a steep learning curve for most engineers to write, and an idiosyncratic syntax (to younger eyes, at least).

However, while it can seem tricky to write Makefiles, it’s relatively easy to use them, which makes them quite a useful tool for getting new team members onboarded quickly. And for my personal projects - given enough time - new team members can mean me! If I return to a project after a time, I just run make help and I can see instantly what my developer workflow looks like.

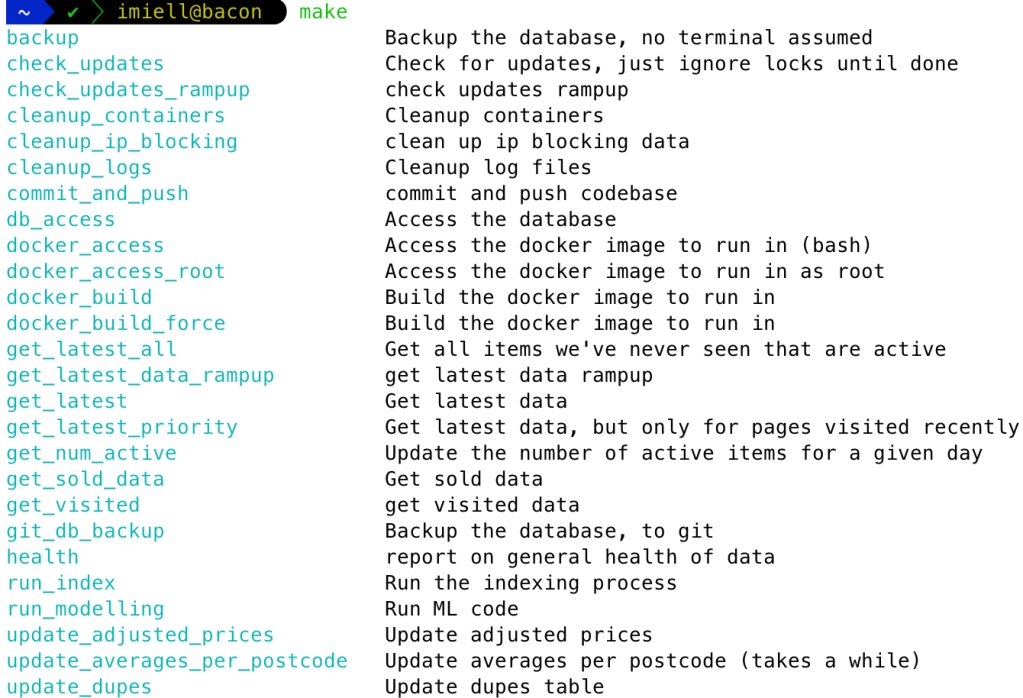

Here’s an example make help on a project I’m working on:

This means if I have to onboard a new engineer, they can just run make help to determine what actions they can perform, and because most of the tasks run in containers or use standard tooling, it should work anywhere the command line and Docker is available.

This idea is similar to Dagger, which seeks to be a portable CI/CD engine where steps run in containers. However, running Dagger on Kubernetes requires privileged access and carries with it a Dagger engine, which requires installation and maintenance. make requires none of these moving parts, which makes maintenance and installation significantly simpler. The primitives used in Make can be used in your CI/CD tool of choice to create a similar effect.

What Low-Tech Devex Tools Should You Know About?

Here is a highly opinionated list of LTD tooling that you should know:

shell

Mastery of shells are essential to LTD; they underpin almost all of them.

vim/emacs

Already mentioned above, vim is available everywhere and is very powerful and flexible. Other similar editors are available and inspire similar levels of religious fervour.

make

Make is the cockroach of build tools: it just won’t die. Others have come and gone, some are still here, but make is always there, does the job, and can’t go out of fashion because it’s always been out of fashion.

However, as noted above, the learning curve is rather steep. It also has its limits in terms of whizz-bang features.

Docker

The trendiest of these. I could talk instead of chroot jails and how they can improve devex and delivery a lot on their own, but I won’t go there, as Docker is now relatively ubiquitous and mature. Docker is best enjoyed as a command line interface (CLI) tool, and it’s speed and flexibility composed with some makefiles or shell scripts can improve developer experience enormously.

tmux / screen

When your annoying neighbour bangs on about how the terminal can’t give you the multi-window joy of a GUI IDE, crack your knuckles and show them one of these tools. Not only can they give you windowing capabilities, they can be manipulated faster than someone can move a mouse.

I adore tmux and key sequences like :movew -r and CTRL+B z CTRL+B SPACE are second nature to me now.

git

Distributed source control at the command line. ’nuff said.

curl

cURL is one of my favs. I prefer to use it over GUI tools like Postman, as you can just save command lines in Markdown files for how-to guides and playbooks. And it’s super useful when you want to debug a network request by ‘exporting as cURL command’ from Chrome devtools.

cloud shell

Cloud providers provide in-browser terminals with the provider’s CLI installed. This avoids the need to configure keys (if you are already logged in) and worry about the versioning or dependencies of the CLI. I agree with @hibri here.

ssh

Why bother with the faffs of remote desktops when you have ssh and tmux? If you depend on GUIs, that’s the problem you need to solve.

Finally, special mentions to these text user interfaces (TUIs) and dev-friendly tools:

Previous article

Previous article