I’ve spent the last three years at cinch establishing a culture of observability, but what does that mean?

The term “observability” was coined by engineer Rudolf E. Kálmán in 1960 to describe mathematical control systems, and has become part of wider control theory. In the software realm, it was popularised by Charity Majors, co-founder of Honeycomb. In their O’Reilly book Majors et al give the following definition:

"Put simply, our definition of “observability” for software systems is a measure of how well you can understand and explain any state your system can get into, no matter how novel or bizarre. You must be able to comparatively debug that bizarre or novel state across all dimensions of system state data, and combinations of dimensions, in an ad hoc iterative investigation, without being required to define or predict those debugging needs in advance. If you can understand any bizarre or novel state without needing to ship new code, you have observability."

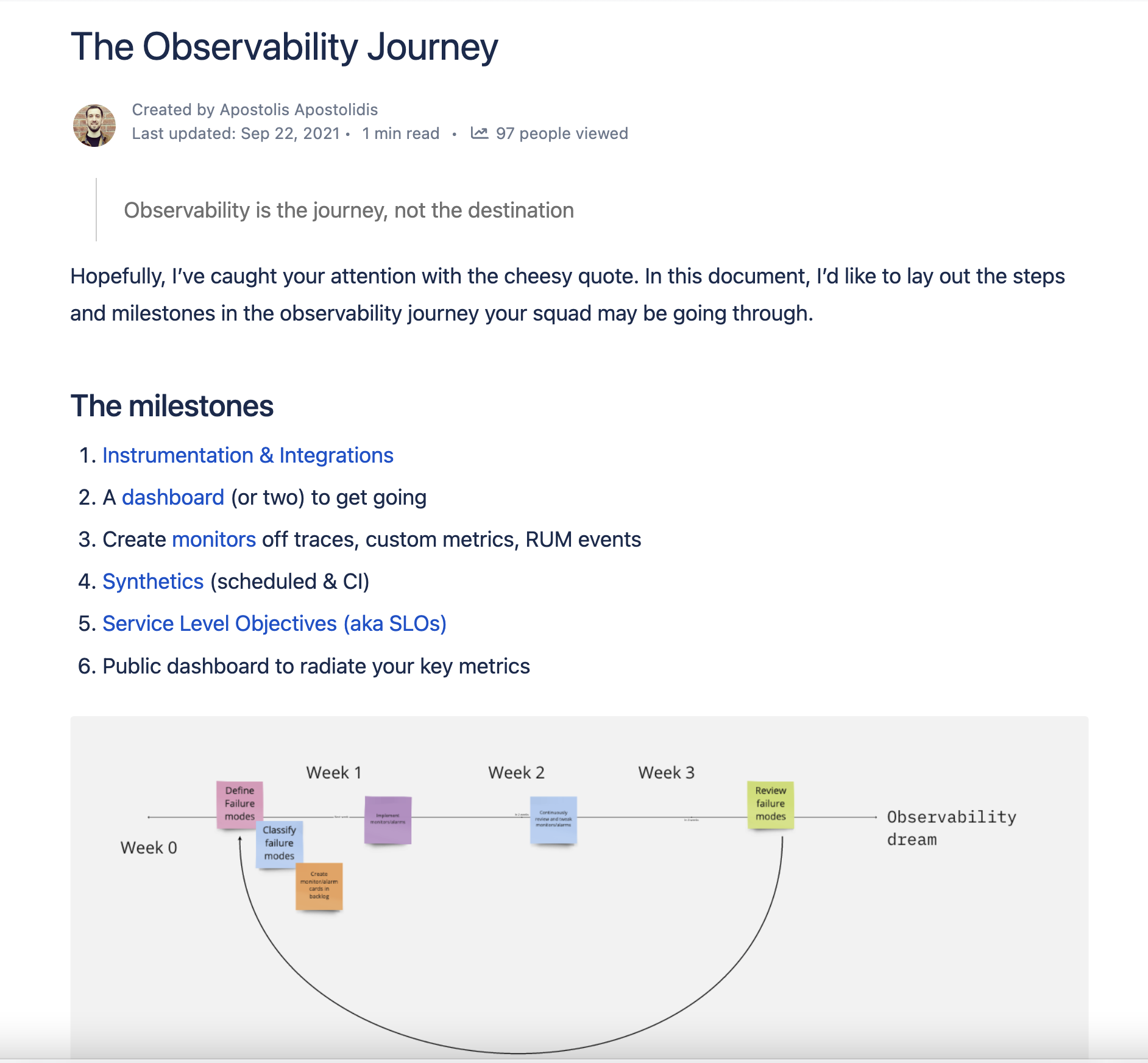

I think a lot of people who decide they need to introduce observability start with a rough plan that looks something like this:

- Choose (and pay for) an observability tool

- “Enable” telemetry data

- Auto-generate the dashboard

- Done!

Unfortunately, like so many other things in the world of Cloud Native, you can’t buy yourself into observability, despite what the various tools vendors will tell you. Whilst picking the right tooling is the first step, there are a number of other things you will quickly need to learn to do.

Picking the right tool could be a whole article by itself, and I won’t cover it in detail here. Suffice it to say that, whilst you can have success with the tooling offered by the major cloud vendors if you are looking to make observability a core practice, you should consider separating your “compute” platform from your observability platform, which implies choosing a specialist observability vendor such as:

- traditional vendors like Datadog, Dynatrace or New Relic

- contemporary vendors like Honeycomb or Lightstep

- Serverless-specific vendors like Lumigo or Baselime.

Being systematic with telemetry data

In traditional logging, the best practice has been to write a generic free text log at the various “entry and exit points” of the code. An example of this is when our code logic runs out of options the most sensible choice is to throw an error. This error will be a free text log like “An error occurred when X happened”. You may include some parameter values that occurred at that point of the code execution. Often, when support cases come in, we retrospectively add log messages to further understand what the code is doing.

There is nothing wrong with this approach per se, but it misses out on a massive opportunity: to understand what is going on when your code is exercised in production.

To make your software observable, you have to view every event in your code as an opportunity to learn. The way to do this is to “annotate” your code so that you can have rich telemetry data. Every entry point, exit point and parameter value can be seen as an interesting data point that you want to add to your telemetry dataset. This data point must be part of a queryable dataset. Think of it as a database schema you are constructing. For example, you would want to have a list of high cardinality key-value pairs rather than a list of random strings. This practice is often referred to as “instrumenting” your code.

With this approach, you have opened up a number of opportunities.

Observability like testability

Does this shift back to the basics seem familiar? To my mind, it feels like there are striking parallels with what we did with testing in the 2000s and 2010s. We realised that we couldn’t change our software frequently unless we had a way of reliably verifying that we were not introducing bugs.

So, we started introducing tests and automation, coming up with practices like Test Driven Development (TDD). We took a massive step back to look critically at how we wrote software, which then enabled something bigger: increasing the rate at which we could safely change the software.

This approach served us well: testable systems allow us to amplify flow, feedback, learning and experimentation. However, we still couldn’t understand the health of our business transactions in production. Observability is the next missing piece of the puzzle that will shift our attention right: to understand the systems that matter.

Sadly, observability is still frequently treated as an afterthought. In a similar way, testability was an afterthought for years before TDD made things like the testing pyramid famous and mainstream. One of the reasons TDD was so successful was because it advocated writing the tests as you write the code. It was finally understood that writing tests later is ineffective and inefficient. In the same way, the practice of instrumenting your code for observability is best done whilst you are writing the relevant code.

Tooling and instrumentation are not enough

There are a plethora of “observability tools” out there nowadays that will help you continuously build a useful telemetry dataset. There is an ecosystem being built for various different use cases, and they will only get cheaper and better over time. However, instrumenting your code for observability and never actually looking at the telemetry data is a waste of time (and money). It’s like having loads of tests but never actually executing them, or shipping the system even if the tests fail.

You have to test the software, not only make it testable. Similarly, you have to “observe” the software. Making it observable is not sufficient. You will have to change the way you approach software engineering if you want to take advantage of your observable software.

As Adrian Cockcroft has noted, observability alone won’t quite cut it.

“…fundamentally, observability as a property means you can construct the behaviour of a system from its externally visible components. So if you have a black box system, if it is exporting enough information about what it's doing that you can predict its behaviour, that is what observability is.

And what we're doing with our systems is trying to get better. So tracing and some of these things definitely give you better observability on what's going on inside a system.

So now you've got this data coming up. The next point is can you make sense of it?”

Our solution to this at cinch has been to cultivate a culture of curiosity.

Being curious

It has to be said that the practice of observability is still not as cool and popular as its testability counterpart. People will not, as a rule, bring it up in interviews to impress, and likewise, interviewers will not ask questions about it.

Because it isn’t a common area of study, my experience is that people will not know where to start with observability. Equally, you may have an existing system in place and an observability approach that is simply not working. Whether you are starting fresh or you are starting off with an existing approach, there are things you have to get right when you first start out:

- Choose the right observability tool for your use case: this is your “observability platform”, your lens into your software. At cinch, we consciously chose to separate our hosting platform from our observability platform. Often using the hosting platform for observability leads you to practices of “log and forget” and sub-par querying capabilities. We wanted to give our teams the best observability experience possible. This has some important security positives, too, as engineers don’t need access to production AWS accounts.

- Democratise the tool, and give everyone access: you can’t establish a culture of curiosity if you don’t make the tool accessible. Prioritise access and ease of use over minor cost savings, as this will benefit the company in the long run. Getting buy-in for this type of investment is a good indicator that the company values democratising understanding.

- Create and promote learning structures: foster a learning culture through things like a Community of Interest (in observability) and working groups. Both of these example structures favour collaborative over individual learning so that people from different teams go on the observability journey together and bring back their learnings to their teams.

- Add observability to the “golden path”. For observability to be taken seriously, it has to be part of the company’s golden path, i.e. the way software engineering is done in the company. Hopefully, testability is on there already.

- Recruit with observability in mind: make observability part of your interview process by telling candidates about the approach and asking them how they know that their software is working in production.

- Design your team structure and roles for observability: design your teams so that they have the support to both make observable software and also learn observability practices. At cinch, we had dedicated roles within each team to support their team develop their observability capabilities.

What practices emerge?

It’s not uncommon to fall into patterns that negatively impact the culture of observing. Namely:

- Only one person knows everything about the telemetry data and the observability tooling

- You have dashboards written in code and following all the “best practices”, but no one understands them or evolves them

- Overusing “infrastructure-level” metrics over business-related telemetry data

- Getting signals of “what” is happening but not being able to delve into the “why”

Once you have established that observability is a team responsibility, you start seeing some emerging practices where teams will:

- Instrument their code by default as they do with testing

- Own and evolve one or more dashboards for their systems

- Review dashboards during stand-ups

- Review dashboards at the end of the day, asking, “does everything seem ok?”

- Take ownership of their alarms

- Have a rhythm of observability improvement katas

- Improve their observability through incident review feedback cycles

- Enable non-engineer team members or those in supporting roles to use the same dashboards the engineers use

Once teams have picked up some experience and momentum with observability, some more advanced practices start to emerge:

- Traces are used as the telemetry unit, and metrics are generated from traces.

- Logs are used in the context of traces or as an exception

- The front end is traced using Real User Monitoring and linked to back-end traces

- Other parts of the system are instrumented such as CI/CD pipelines and security

- Teams start creating and owning Service Level Objectives (SLOs)

There are a few signs that indicate observability maturity at the organisational level:

- Observability blueprints emerge that serve as “the way to make your software observable”

- Self-sustaining observability Community of Interest flourishes

- Subject matter experts in observability emerge from existing engineers

- Most engineers are skilled observability practitioners—instrumentation and using the observability tool are core skills

- Non-techies know about observability in the same way that they know about testing. In fact, it’s more relevant to them as they can probably use the tool more easily!

Observability enables DevOps

The best thing about observability is that it’s vague. It can take any shape or form—despite what they might tell you about 3 pillars or wide, high cardinality events. Suddenly you have a large part of your company actually curating your software’s telemetry data and asking questions a single software engineer’s test suite simply can’t answer with confidence.

Who instruments the software better?

Instrumenting your code effectively creates a highly-reliable telemetry dataset that represents what is happening to your software when exercised by real data—real requests and user actions and views.

In a way, it’s a very similar practice to what we typically know from analytics or data intelligence. To get analytics for your website or data intelligence for your software system, at some point you have to insert markers into the system (analytics) or extract and transform it as an external observer (data intelligence). Both of these result in a dataset of sorts that can be visualised in an appropriate manner depending on the use case. In a way, these approaches were making software observable before this new hip wave of observability came along. The big difference between these two approaches and observability is two-fold:

- The creators of the data are not the curators of the data

- The creators of the data are not the consumers of the data

As a result, the data gets out of sync with reality, and you end up with a DevOps anti-pattern where software engineers write code and throw data over the wall to analysts or data analysts.

This is where observability has the potential to blur the lines. Rather than analytics and data intelligence initiating the “data creation”, the builders themselves create and care about the telemetry dataset. As a result, it can be used by anyone irrespective of their discipline: Analytics, Data, Product etc. We have started to see this “blurring” of the lines happening in contemporary observability tooling, with analytics features like funnels or data intelligence features like data pipelines and data dashboards.

Observability is a bigger deal than testability

Observability is bigger than its counterpart, testability. Testability enables rigorous lab testing, whereas observability enables widespread field testing. At this point, I’m not sure the word “testing” is relevant anymore.

Testable software allows you to assert the health of the “happy paths” in your code automatically—and occasionally the “unhappy paths”. You would typically make these automated assertions whenever the team changes the software. It’s a contract between the team that owns the software and its users:

“I promise that I will change the software, and it won’t get worse. If anything, it will be better.”Observable software allows you to assert the health of your business transactions. The assertion, in this case, can be both manual and automatic and can be made either when you make a change or at any other point in time. It’s a contract between the team that owns the software and its users:

“I promise that you will have a service, and you can rely on me. If I make a change, I promise that your service will get better, and I will know if it doesn’t.“

Although it is fair to say that testable software does, at times, bring software engineers closer to their customers, observable software is, I’d argue, the ultimate “shift right” nudge. With observable software, software engineers are not solely working in a lab anymore, they get a glimpse of the field—the real world. And they are taking the entire organisation on the journey with them.

Previous article

Previous article